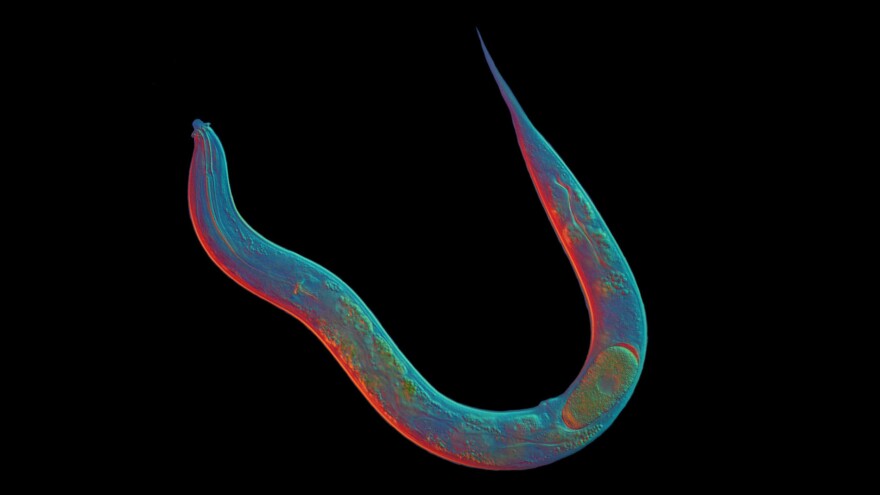

Abstinence may have found its most impressive poster child yet: Diploscapter pachys. The tiny worm is transparent, smaller than a poppy seed and hasn't had sex in 18 million years.

It has basically just been cloning itself this whole time. Usually, that is a solid strategy for going extinct, fast. What is its secret?

"Scientists have been trying to understand how some animals can survive for millions of years without sex, because such strict, long-term abstinence is very rare in the animal world," says David Fitch, a biologist at New York University. Most plants and animals use sex to reproduce.

As he and his colleagues report in the recent issue of Current Biology, this seemingly unimpressive roundworm seems to have developed a different way of copying its genes — one that leads to just enough mutations to give the worms room to adapt, but not enough to cause crippling defects.

Sex is pretty great for a lot of reasons (unless, perhaps, you're a duck), but one is that it's a good way to dodge the effects of bad mutations.

"All organisms accumulate mutations," says Kristin Gunsalus, a developmental geneticist at New York University and a co-author of the study. Usually, the machinery that copies DNA makes a few mistakes each time a cell divides. In humans, says Gunsalus, there are about 0.6 errors per cell division.

"The general thinking is that 'bad' mutations accumulate and become concentrated if genetic diversity is not maintained," she says. Sex is thought to help prevent what some researchers have called "mutational meltdown."

Sex allows organisms to mix and match genes, helping species adapt to changing environments. Studies in organisms that can reproduce sexually and asexually have found that sex helps a species adapt to dangerous parasites and shrug off bad mutations.

"Generally, people think that the great innovation of animals and plants — eukaryotes — is that they've evolved sexual reproduction," says Gunsalus.

But sex is also a lot of work. For one, you have to find a mate. You often have to spend time and resources competing with others to get the mate. And only half the population — the females — are capable of reproducing. It's really inefficient.

"I mean, why bother with all those males and all that rigamarole?" says Benjamin Normark, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who studies the evolution of unusual genetic systems, mostly in tiny insects. He wasn't involved in the study.

Imagine, Normark says, two species that are identical, except that one makes babies by having sex and one makes babies by copying itself.

In the sexual group, he says, "Females are harvesting resources and turning them into eggs. Males are spending their energy competing for access to mates most of the time."

The asexual population doesn't have to worry about all that stuff. All they have to do is make copies of themselves.

"The asexual population would have twice the birthrate because every single individual would be having babies," he says. "So, the asexual population would outcompete the other one very quickly." It's a huge advantage.

So, is everything we think we know about sex wrong?

Maybe.

"It makes it very paradoxical that anything is sexual — let alone that everything is sexual," says Normark.

"Except the thing is, [asexuality is] so rare," he says. So rare that, when scientists started finding males among various species that were thought to be completely asexual, Normark almost stopped believing long-lived asexual species really existed.

But every now and then, something like D. pachys comes out of the woodwork. D. pachys hasn't had sex for millions of years and it's just fine.

Still, that doesn't mean it was always so self-sufficient.

After sequencing the worm's genome, the researchers concluded that the asexual roundworm actually had sexual beginnings.

Once upon a time, about 18 million years ago, there was a more typical type of tiny transparent worm.

"Happy-go-lucky, male and female, dating on a regular basis," says Gunsalus.

And then, well, no one really knows what happened.

Somehow, the worm fused its ancestors' six pairs of chromosomes into one pair of huge chromosomes. It did away with a major step of meiosis — the part of the reproductive process where chromosomes reshuffle before splitting into two cells.

It ditched sex in favor of precise, simplified cloning.

And so began D. pachys and its cousins — basically, clone armies of sexless worm species. They eat bacteria and can be found in soil all over the world.

And so far, they're doing OK.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMzY5MzE4MDEzMTE3ODg5NDA4ZjRiNg004))