Audri Robbinson is worried about her kids. Like many parents, she became a second teacher to them after state leaders announced in-person classes would be temporarily suspended in March. But it's been an ongoing challenge to keep Vincent, 4th grade, and Viauna, 2nd grade, engaged outside the classroom.

Now, she thinks they may be falling behind, succumbing to what some are calling the COVID-19 slide.

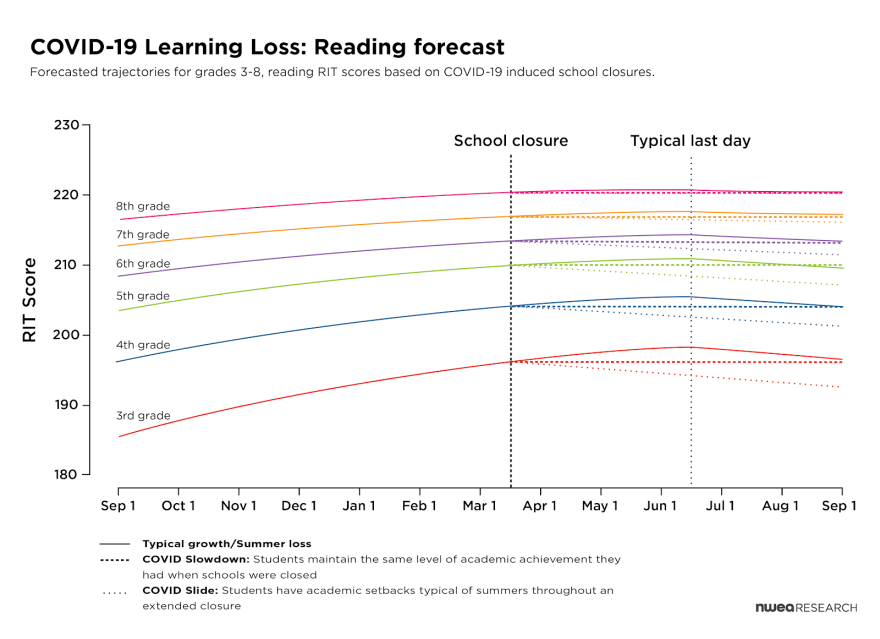

There’s usually a summer slide every year, where students forget or lose some of the material they learned the previous year.

And with students missing out on a few months of in-person classes, the slide could be even worse this year.

The Robbinsons live in Ogden, but the kids go to Rose Park Elementary school in Salt Lake City. For each of them, online learning has been frustrating. Robbinson said there are too many apps and programs, and it’s hard to stay focused.

She’s also a single mom and works full-time, so only has two days each week to make sure her kids are doing what they need to. And because she has a learning disability, she sometimes has trouble helping her kids when they don’t know how to do something.

“They're teaching me as I'm teaching them,” she said. “And I just feel like I'm failing because I don't know the answers to their questions sometimes.“

Heidi Matthews, a teacher and president of the Utah Education Association, said the slide probably won’t affect all students, but for those it does, it could be a difficult hurdle to overcome.

“I think of an English language learner,” said Heidi Matthews, a teacher and president of the Utah Education Association. “Losing these additional 3-4 months in addition to what would happen in the summer, that's huge.”

Matthews said the students who will be worst off are the ones who teachers already knew were struggling — such as those English learners, as well as special needs and low-income students. But now there is the added group of those who haven't been engaged during this pandemic.

The numbers vary from class to class, but many teachers have reported lower or spotty attendance since the pandemic began. Some students — like Vincent and Viauna — can only check in periodically. Some never showed up at all.

That’s why Salt Lake City Superintendent Lexi Cunningham said one of the major goals this summer will be assessing kids to see what they’ve been able to learn and retain through the pandemic. One idea is to bring in small groups of students over the summer to work directly with teachers on the areas they need most help with, but she said there is no concrete plan yet.

What actually happens — as well as what the start of the next school year will look like — will mostly depend on the risk posed by this new and unpredictable virus. Cunningham said the district, like the rest of the state, will have to have several plans in place based on whatever the health guidelines are at the time.

As for next year, “we've already talked about maybe doing school every other day and bringing in one group of students on this day and another group another day,” Cunningham said.

According to the latest version of the state’s plan for reopening the economy, schools are planning to bring students back in the fall. Desks may have to be spaced farther apart, and teachers and students might have to wear masks.

Schools may also face “waves of stopping and starting, partial or staggered openings, other scheduling adjustments such as earlier or later start dates and times, or other developments determined by local health departments, population vulnerability, and more.”

Almost every scenario, however, will involve more online learning. Cunningham said that means districts will have to help students and teachers build those skills.

“We have to teach people how to learn online,” she said. “And I think that may be just some lesson planning that we need to do when we have students return to school.”

Because school closures happened so quickly in March, not everyone was ready for the transition, she said. But now, there’s an opportunity to get it right.

UEA President Heidi Matthews said the pandemic could help make education a more personalized experience. Using both online and in-person classes, for example, could help teachers give different lesson plans to students in the same class, so they’re all learning at their own pace.

“It forces us to begin to look at how we're going to do that,” Matthews said. “And it encourages the conversations more and requires the action, which really starts with funding.”

But with so much economic turmoil in the wake of the pandemic, school funding is yet another hurdle to tackle.

Utah public schools are getting $67.8 million from the federal government to cover COVID-related costs — things like moving classes online or more cleaning that schools will have to do next year. But because state income tax funds the education budget, with record levels of unemployment, that could be taking a hit as well.

After a request from the state Legislature, the Utah State Board of Education board has recommended cuts to the budget, adding up to around $380 million in potential losses. The suggestions will be considered at an appropriations committee hearing Wednesday morning, with a final decision to come at a special legislative session next month.