It was nearly 7 in the morning as Elsa Gonzalez got her 8-year-old daughter, Yareli, ready for school. The sun was beginning to come up outside, as she brushed her hair and handed Yareli a glass of warm chocolate milk.

Gonzalez is a small woman who has her raven-colored hair slicked back into a low bun. She’s a working mom who cleans houses around the valley and cares deeply about her daughter’s education.

She moved quickly around the house, keeping her eye on the kitchen clock as she made sure she had everything ready for the day. Backpack? Check. Car running? Check. Breakfast served?

Check. Check. Check.

The commute to Mountain View Elementary School used to be a short walk away. But almost a year and a half ago, Gonzalez was forced to move out of the two-bedroom home she rented in Salt Lake's Glendale neighborhood on the west side of the city.

Over the last couple of years, the West Side has gotten pricier as new developments come in and raise the cost of housing. The city has even created a gentrification study to better understand the impacts of these displacements.

When Gonzalez couldn’t find something in her price range in the community, she moved to West Valley City. Now, the trip to school is about a 15-minute drive on Interstate 215 on a good day when there’s no traffic.

“I didn’t want to move here,” she said. “But I couldn't find a place to live close to the school and my [older] daughter found this on the internet.”

She enrolled Yareli at the nearby elementary school but it wasn’t a good fit for them.

“I didn’t like it. One, because I felt that there was a bit of racism and it was very difficult for me to communicate in Spanish with [teachers] — for any question I had,” Gonzalez said. “And another because there weren’t activities like there are in Glendale and Mountain View.”

So after six months — she decided to re-enroll Yareli back into her old school.

As the coordinator for the Community Learning Center in Glendale, Keri Taddie works closely with students and families from both the elementary and middle schools. She’s seen a lot of people like Gonzalez and her daughter who have been impacted by displacement in the last couple of years.

“We're losing students at an incredibly rapid rate because they're moving out of the neighborhood and moving to other communities where housing is more affordable,” she said.

That loss impacts the funding schools receive. According to Taddie, the state uses a formula based on the number of students enrolled in October to determine how much money schools get. She said it also affects their ability to provide popular programs like dual immersion, which teaches lessons in Spanish and English with the goal of students becoming literate in both languages.

But most importantly, she said it disrupts student learning.

“Here we are trying to create a space, with consistency and ensure that our students have support [here] and then also have access to all the other experiences that they need to be successful,” Taddie said. “And when you're displaced, all those relationships it's harder to keep, it’s harder to stay connected.”

The majority of schools on the west side of Salt Lake City primarily serve newly arrived refugees, low-income families and Latinos.

Schools like Mountain View offer programs targeting Latino families like Padres Comprometidos. A course that helps parents engage in their children's education.

Rick Brammer, a demographer with the consulting firm Applied Economics, was hired by the Salt Lake City school district to look at enrollment. He presented his findings in a report to the school board in January.

Brammer found that enrollment has declined significantly over the past few years. Some of that was due to the pandemic and fewer births but he found that it also has to do with displacement as a result of gentrification.

“Economic growth is fantastic. A lot of housing growth,” he said at the school board meeting. “But the nature of that growth is shifting away from the school age population. It's a good thing from a community development standpoint. It feels good, it looks good, but it's hard on families and it displaces people.”

His analysis, while not comprehensive, looked at a sample of 4,600 apartment units in the downtown area and found fewer than 100 students enrolled in the district.

The report identified that developments in the area have continued to appear at a rapid rate over the past dozen years, but these “projects generally do not offer amenities to and are too expensive for, families with children.”

“It's not just the number of units… it's the change in what they're building. I didn't see anybody who was talking about playgrounds and swing sets,” he said. “I mean, we're talking about workout rooms and coffee bars, all that kind of stuff that adults generally want.”

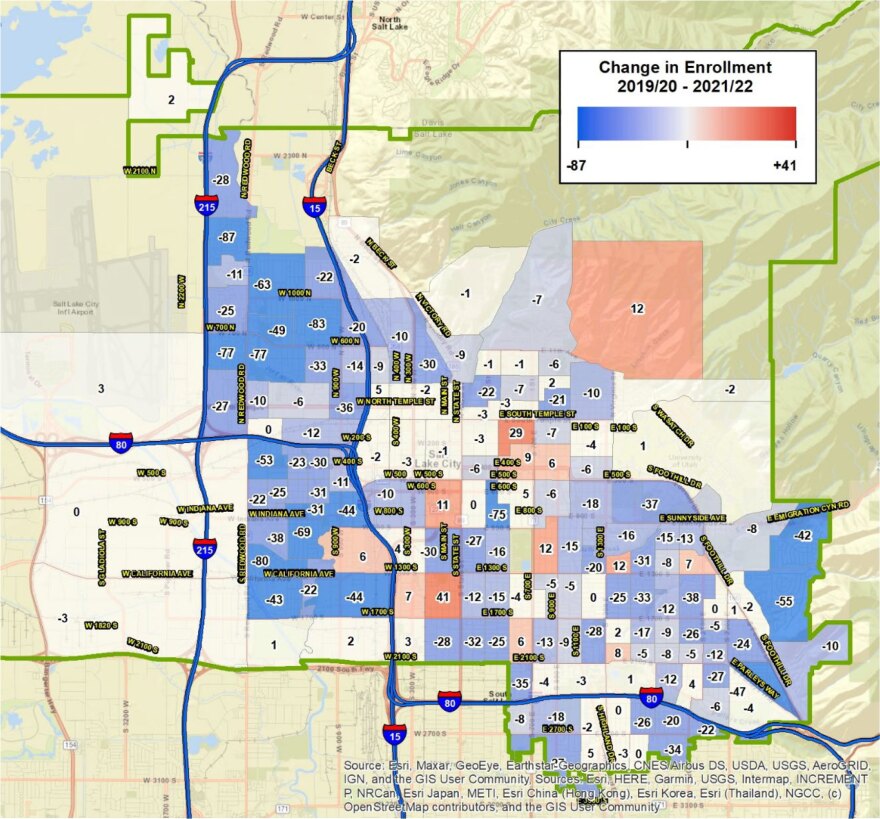

Brammer also pointed out that the schools that are being hit the hardest are west of I-15. He projected that enrollment will continue to steadily decline in the coming years.

Elsa Gonzalez acknowledged it’s a struggle to wake up at 6 in the morning and travel twice as far as she used to just to bring her kid to school. She also knows not many parents can do it.

It's a sacrifice that she’s willing to make for her daughter’s education.

“The future of my daughter, sometimes it does affect me. But I say, 'no, I gotta take her.' Sometimes I say no more, maybe one of the closer schools on the corner. But I don't feel comfortable there,” she said. “Taking her to the other school, it’s better to make the effort even if I make more trips or waste gas. But God will help me.”

For now, though, she’ll keep driving her daughter back to school.