The drive behind a massive water development project in southwestern Utah, the Lake Powell Pipeline, shows no signs of slowing even after the Colorado River Basin states signed a new agreement this spring that could potentially force more conservation or cutbacks.

Despite the risk that the river resource is overcommitted and it is shrinking, four Upper Basin states — Utah, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico — are pushing forward with dams, reservoir expansions and pipelines like the one at Lake Powell that will allow them to capture what they were promised under the 1922 Colorado River Compact. The Lower Basin states of Arizona, Nevada and California have been using that water downstream for nearly a century.

President Donald Trump signed the basin-wide drought contingency plan in April, just weeks after the state of Utah declared in a news release that the river, which serves 40 million people, is “a reliable source of water.”

“What they need to do — the lower states — is use their right that's allocated to them, and we will use our right that’s allocated to us,” said Mike Styler, who retired recently after 14 years as director of the Utah Department of Natural Resources.

A former state lawmaker, Styler originally voted on pushing forward with the 140-mile Lake Powell Pipeline. Once completed, the diversion project, which would draw from the lake, which straddles the Utah-Arizona border, about 86,000 acre-feet a year. That’s enough water to support nearly 100,000 households.

Gary Turner, a Washington City turf farmer, said he supports the project as a way to allow continued growth in southwestern Utah.

“We absolutely have to have it,” he said on a recent spring day as he prepared to harvest 42 pallets of sod for customers around the region. “I don’t know of any other option.”

Houses and apartments have sprouted up around Turner’s 114-acre farm — evidence of a population boom that’s been underway in southwestern Utah for years.

The St. George metropolitan area was the third-fastest growing in the nation last year, according to U.S. Census Bureau data released in April. Past data showed the area as the fastest growing in 2017 and the fifth-fastest growing between 2010 and 2018.

Pipeline proponents anticipate the trend will continue, with the current population of around 171,000 residents expected to swell to around 509,000 by 2065. And that growth is why they insist the pipeline is necessary.

Turner said he’s concerned about having homes for growing families and the demand for lawns drying up if water constraints stifle the boom.

He irrigates the vast expanse of his manicured green grass with water from the Virgin River, now the area’s sole source. He said pioneer-era water rights provide what he needs to maintain his farm, so he doesn’t need more water from the pipeline to stay in business. But Turner said more water will be needed for the community’s expansion and for the lawns they’ll need.

“We grow houses better than we can grow any other commodity,” he said.

The state has already spent more than $30 million on its application to build the pipeline. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is currently reviewing the project’s environmental impacts. The Washington County Water Conservancy District, a project partner, estimates that the license could be finalized in two years, construction would begin a few years later and the pipeline would be operating by around 2030.

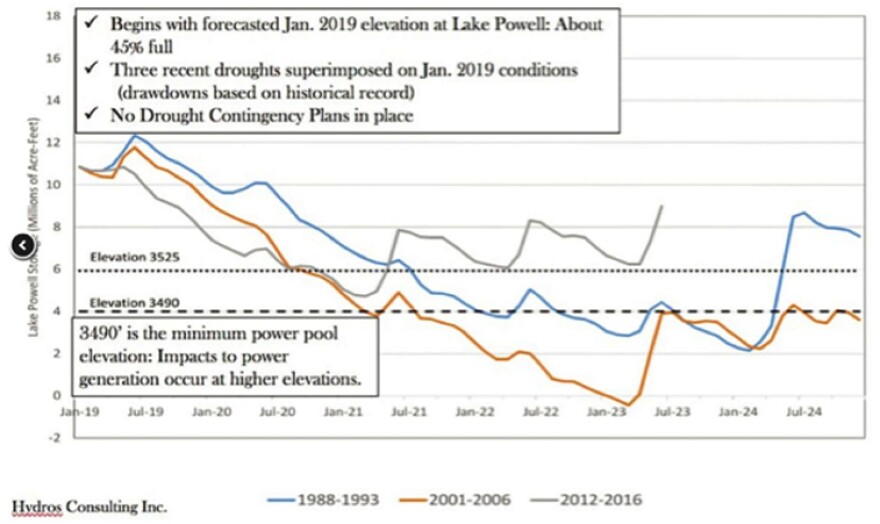

But pipeline critics call the project too risky, too pricey and unnecessary. They contend that too much Colorado River water has already been promised to too many people.

“We are way beyond the budget of what the Colorado River can deliver, and when you just look at how much water is in the river and how much everyone else wants to take out, it's just not there,” said Nick Schou, conservation director for the nonprofit Utah Rivers Council.

Schou said the Lower Basin states are facing cuts of as much as 500,000 acre-feet at the same time the Upper Basin states are planning nine projects that will draw about 400,000 acre-feet.

“Not only are we overusing the water, but there's going to be a lot less to go around in the future,” Schou said.

Instead of a pipeline, opponents insist the smartest and cheapest solution is conservation.

“We don't think there will be the water,” said Lisa Rutherford, who tracks the pipeline proposal for the nonprofit, Conserve Southwest Utah. “We do not think that we need the water.”

Rutherford said she’s worried that pipeline proponents will hinder sorely needed efforts to conserve water — efforts that are already stymied by low prices for water in the St. George area.

A survey last summer by KUER compared what customers pay in other Western cities for 28,000 gallons of water, the average used by St. George residential customers in July. Las Vegans paid $111. In Denver, the cost was $144, and Tucson residents ponied up $235. But, in St. George, the bill was $61.

The project’s overall cost is another big concern for critics. Proponents estimate the pipeline’s cost between $1.1 billion and $1.8 billion. Critics say the price tag will probably be $3.2 billion or higher. And water users would be saddled with the cost, since the what used to be common federal subsidies for big water projects have evaporated.

Rutherford’s partner, former state Attorney General Paul Van Dam, said the roots of the controversy go beyond facts and figures. He said many Utahns hold the conviction that Nevada, Arizona and California have been allowed to take precious resources that belong to Utah.

“That's just absolutely almost part of the DNA of people out here,” Van Dam said. “And - and it's just like treason if you don't fight for the water that is your water.

This story is part of “The Final Straw,” a series produced by the Colorado River Reporting Project at KUNC, KUER and Wyoming Public Radio.