Around the country mounting distrust of vaccines has created an opportunity for diseases to spread that previously disappeared from the United States. Measles was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. However, this year there have been 981 cases nationwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Whether people rely on scientific data or emotional anecdotes to inform their views, conversations about vaccines can have a significant bearing on the public’s view of their safety, according to a new study out of Brigham Young University.

Around 70% of individuals who were hesitant about the safety of vaccines changed their perspective to becoming pro-vaccine, after talking with someone who had a vaccine-preventable disease, according to findings in an article by Brian Poole, an associate professor of microbiology at BYU.

According to Poole’s study, personal stories are powerful determinants of what people think.

“The anti-vaccine people have used it very effectively. They tell their stories. It’s all very personal with them,” he said.

The study evolved from what Poole witnessed over several semesters teaching a class called Infection and Immunity. In their class evaluations, students described skepticism about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. The hesitancy corresponded to national trends of people opting out of vaccines that had been troubling to the professor for years.

“I personally have been upset about it for probably 10 years or so,” Poole said.

As he watched personal anecdotes of children having allergic reactions to vaccines spread online, Poole wondered, could emotional stories be used to show the benefits of vaccines too?

“I think that as scientists, a lot of the time we have the truth, but we don’t have very good stories to go along with it,” Poole said. “It’s very hard to tell a story of a million people who got vaccinated and nobody died. It’s a true story, but it’s not a great story.”

Last year Poole and one of his graduate students designed a study to test this communication dilemma. They enlisted around 500 BYU students to interview people who have had vaccine-preventable diseases including polio, tuberculosis, meningitis and shingles. Many of those interviewed were older, and had lived during a time when these diseases were more prevalent.

The student participants ranged in perspectives, but Poole focused on those who had skeptical attitudes towards vaccines.

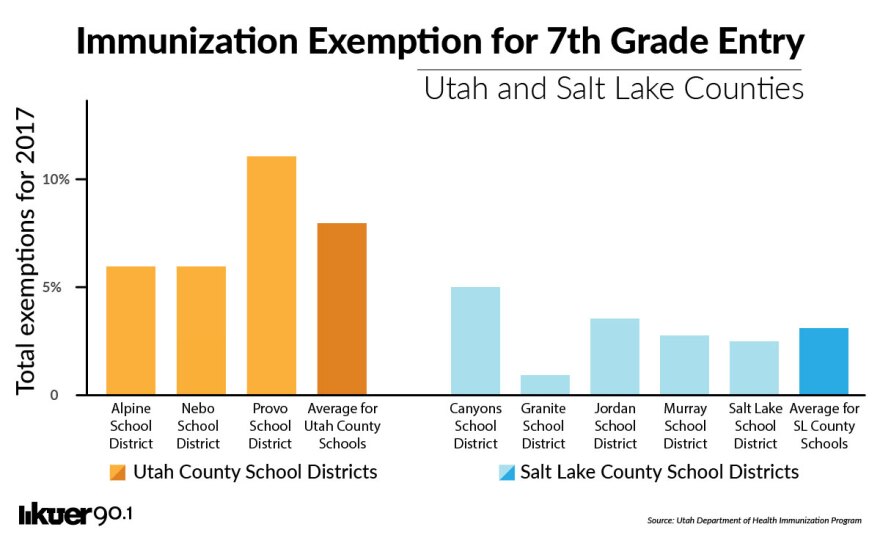

According to a 2018 article in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS Medicine, the Provo metro area — the home of BYU — ranks sixth in the country for parents who exempt their children from vaccinations. The Utah County Health Department lists the county average of students who are exempt from immunizations at 4.68%. However that doesn’t give the full picture, according to local public health officials.

“There are pockets, there are schools, there are areas of different towns in Utah County that have exemption rates that are much higher than that,” said Jody Carly, a nurse with the health department.

Data from the Utah Department of Health’s Immunization Program shows some school districts in Utah County have exemption rates four times higher than those in Salt Lake County districts.

Utah County is largely Mormon, but that’s not the driver of this vaccine hesitancy. Officials with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints have urged members to vaccinate their children. According to church spokesman, all missionaries are required to be vaccinated and LDS charities does immunization campaigns worldwide.

A 2008 television clip from KUTV News shows the late church President Thomas S. Monson discussing being vaccinated before traveling to Panama to dedicate a new temple.

“Had all my shots. In both arms,” Monson jokes to the news anchor.

The more likely reason for this skepticism, said Poole, who is Mormon, is that vaccines are so effective, no one sees the diseases anymore, and protection doesn’t seem as important. In middle-class cities with cultures that prize naturalness the risk is diminished, he said.

Public health officials worry that’s contributed to this year’s nationwide measles outbreak, none of which occurred in Utah.

There are clusters of people who don’t vaccinate in conservative Provo just as there are in liberal Portland, Ore., the site of a measles outbreak this year.

“Being anti-vaccination is actually kind of equal opportunity conservative and liberal. The conservatives don’t like it because the government is pushing it and the liberals don’t like it because [of] the pharmaceutical companies. You can always find a bad guy,” Poole said.

Countering misinformation about vaccine risks in person and online is not something doctors or researchers have done very effectively, says California physician and writer Dr. Rahul Parikh.

“I think we need to sort of pound the pavement in a way that allows us to go where people are hearing those messages and counter them using these kinds of stories,” said Parikh, who has written about the need to use more emotional arguments in favor of vaccines.

Parikh described the successful public health campaign against tobacco in which powerful, personal stories were used with strong effect. He says the same could be done with vaccine messaging.

Poole from BYU says his research could help focus public health messages. For example, instead of focusing on the safety of vaccines, campaigns could focus on the danger of measles.

While there is risk in describing science using anecdotes and emotional stories, it’s worth it, Poole says.

“If you don't combine the information that we’ve got with stories to make it meaningful to people, then it's kind of useless. It doesn't spark any desire to do anything.”