Some might recall the summer of 2007 for its top billboard song or action-hero movie, but for Utah's public pool-goers that summer stood out for unhappy reasons.

An outbreak of cryptosporidium, a single-celled parasite, sickened thousands of Utahns in the summer of 2007. Nasty infections sent 97 people to the hospital. And, in the years since, Wasatch Front counties have responded by upgrading equipment and procedures to make pools healthier and safer.

But KUER's investigation of pools, spas and splash pads shows that the biggest problems trace back to patrons. We learned this by poring over inspection data from the four Wasatch Front health departments. The agencies oversee 2,073 recreational water sites - any facility that's used by four or more households or the general public.

Making sure users practice good pool etiquette is at the heart of many of the hundreds of complaints filed at the health departments over the past few years.

A Cautionary Tale

But, to understand how the current system evolved, it makes sense to look at the national crypto outbreak in 2007 that was concentrated in Utah. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimated about 8,300 cases nationwide that year. And the CDC described Utah's confirmed 1,902 cases as one of the largest outbreaks in U.S. history.

That year, cases began popping up in May and ramped over the summer. The signature symptom of a crypto infection is diarrhea. But nausea, vomiting, fever and stomach cramps are also common.

No one died in Utah from crypto in 2007. However, many patients were very young and sick for weeks. Nearly one-third of the confirmed cases involved children under age 5

The outbreak peaked on Aug 19 . And, nine days later, state health officials took the unprecedented step of banning children under 5, and anyone else in diapers, from public pools.

Michelle Cooke described drownings as her biggest fear in the facilities she oversees for the Weber-Morgan Health Department. But she called crypto outbreak "a nightmare."

Reflecting on Utah's cases, health officials noted that four of every five people with confirmed cases had visited at least one recreational water facility in the two weeks prior.

Crypto often spreads when someone comes in contact with the stool of somebody who already has it. And even the tiniest amount ingested from a pool or spa can make lots of people sick.

"I don't want to say [we had a] helpless feeling, but it felt like unless the public was willing to take on some of the onus, there was very little that that could be done other than education," said Jason Garrett, now director of the water quality bureau at the Utah County Health Department.

"There were just hard decisions to be made."

Lessons Learned

State and county health departments have, in the years since, updated pool health and safety programs with 2007 in mind.

"I think — especially after the crypto outbreak we had — kind of woke everybody up to the fact that there are potential risks like that," said Cooke, of Weber County.

Inspections continue to be a first-line defense in Utah.

Warm-season pools, spas and splash pads get inspected before they open each year. Large facilities typically get monthly spot checks. Health or safety problems found during these visits trigger follow-up from the health department inspectors.

"Public safety is No.1," said David Duckworth, an inspector for the Salt Lake County Health Department. "We just make sure the water quality's good, the pool's safe for people who use the pool and that the public's protected. That's our goal."

Health department inspectors routinely check the ultraviolet filters at recreational water facilities. Chlorine doesn't always kill crypto. But UV does, so ultraviolet filters are required at splash pads now, and most large pools have them too, Duckworth said.

"As long as it cycles the water through the pool, that entire volume, you're able to have a pretty good guarantee that it's going to inactivate crypto, and you're not going to have a spread," he noted.

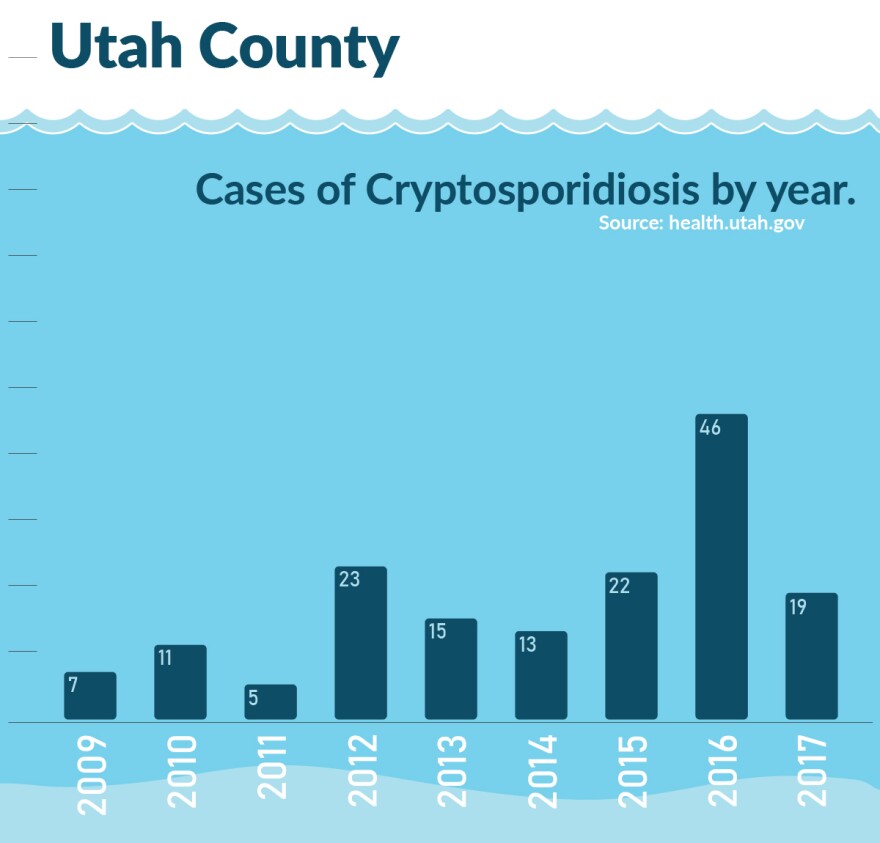

The Utah Health Department also stepped up its crypto record-keeping and posts data online. The confirmed cases from the summer of 2007 have always been considered undercounted, since many people don't go to the doctor for diarrhea. Now the health department puts the number of crypto cases that year at closer to 3,500. In contrast, the statewide average from 2012 through 2016 is 144.

The Trouble With Chlorine

But more than 300 complaints reviewed by KUER showed that recreational water facilities on the Wasatch Front still have health and safety problems. Patrons report everything from foul water at a hotel to rashes blamed on fitness center hot tubs.

One extreme example was a 2014 complaint to the Salt Lake County Health Department about finding a dead body at the Northwest Rec Center in Salt Lake City. A staffer arrived to open up the pool and discovered the corpse of a man who’d broken in overnight. The police report does not list a cause of death, but the man was still dressed in street clothes.

Overall, the complaints reflect how a system designed to protect is falling short because of the people using recreational water facilities.

And officials use several strategies to combat the problems. One is behavior engineering. That’s the purpose behind periodic breaks at most public pools, when lifeguards tell all of the swimmers to get out of the water.

“During the five-minute breaks, it's really important that everyone tries to use the restroom, because we do find that a lot of families have a hard time getting their kids out of the pool in the middle of that hour,” said Patty Kittrell, aquatics director at the Northwest Rec Center. “If we can get everyone to use the bathroom every hour, it definitely helps cut down on those contaminations that we get.”

The word “contamination” here is code for urine, feces and sweat, the human contaminants that undermine the effectiveness of the chlorine disinfectant. In fact, they can dirty the water so badly that the chlorine undergoes a chemical reaction that can generate nasty fumes called “combined chlorine.”

“It's kind of a fallacy that people think when they go into an indoor pool and they smell chlorine — a strong chlorine smell — they think that's a good thing because it means there's chlorine,” said Dave Spence, deputy director of the Davis County Health Department. “In fact, that's kind of a bad thing, because it means there's a lot of combined chlorine, which means that the chlorine is ... bound up to things that are in the pool.”

Combined chlorine can be a serious problem, as one report to Spence’s agency showed.

During a children’s swimming championship last March at the South Davis Rec Center in Bountiful, the chlorine smell became overwhelming. Officials and competitors at poolside complained their eyes stung. They had trouble breathing. One competitor even went to the hospital in an ambulance.

The dirty water had created dirty air. Officials realized that the people in and around the pool were causing the problem. So, they nudged competitors to clear the pool deck, shower and remove clothing that was choking the ventilation system.

“I think because it’s fairly common, sometimes people think, ‘Oh, well, that's just what it is’,” said Cathy Vaughan, who oversees safety for Utah Swimming and who served as a referee at the championship meet in March. “But it got to the point where it was a real concern for the health and safety of people who were there.”

She added: “I just think that we just have to learn what we're up against.”

Education is an important tool to promote health and safety at pools and spas. But people evidently ignore simple guidelines about not urinating in the pool, showering before they swim and staying out of the pool if they’ve been sick lately.

Utah health and swimming officials keep searching for solutions that stick. But their job is tough: getting patrons to embrace the awkward message that pee, sweat and diarrhea don’t belong in the places they’re swimming. It’s not advice that’s easy to put a positive spin on.