North Salt Lake is home to one of the last medical waste incinerators in the country. Stericycle, the company that operates the incinerator, came under scrutiny this summer after state officials cited it for violating emissions standards. Residents of the Foxboro neighborhood became concerned about this plant operating next door. Many bought homes there without knowing that pollutants were being released into their neighborhood. In the first of a two-part series, What’s Burning in the Backyard, we tell the story of how Foxboro grew up around a medical waste incinerator.

We start our story with some Foxboro residents, who live just across the street from Stericycle’s medical waste incinerator, Dan and BeccaHubrich and their three children just home from school, bouncing on a trampoline in the backyard.

Just behind those bobbing blonde heads, there’s a white plume of smoke that kind of looks like steam. When Dan and Becca decided to build a home in Foxboro more than six years ago, the new neighborhood seemed ideal for a young family.

“We really were drawn to the community,” Becca says. “We knew this would be a community with a lot of young families. There was a lot of appeal, they have a lot of parks, there was a lot of togetherness, the homes are kind of close knit."

Becca’s husband Dan liked the location – the convenience of being right between I-15 and Legacy Parkway. The Hubrichs say their neighborhood is all that they had hoped for, but they did wonder why they would sometimes see black smoke coming from the plant across the street.

“You know our kids would say mom, the building's on fire again," Becca says. "And we would always say that can’t be good, but we had no idea what it was, until we went to a city council meeting, and they had a team of doctors telling us – telling us what a medical incinerator was, what they were burning, and what that was polluting our air with.”

"You know our kids would say mom, the building's on fire again." - Becca Hubrich

City leaders held this meeting because the state division of air quality cited Stericycle in May this year for exceeding permitted levels of pollutants like dioxins and for falsifying the results of stack tests. Becca and Dan learned that dioxins are a highly toxic byproduct of burning plastic –that they can cause cancer, and affect human fertility and development.

The Hubrichs’ learned that even when operating the incinerator legally, Stericycle is allowed to release limited amounts of these dioxins, as well as lead, mercury, and nitrogen oxide. They also learned that the black smoke they saw a few times a year was an emergency bypass incident. That means waste is released directly into the air without any of the usual filters.

“I was upset, I felt deceived,” Dan says. “The two things I was upset with was why was I not told this from the beginning? And the second things that made me upset, how did they get a permit to build right next door to this thing in the first place?”

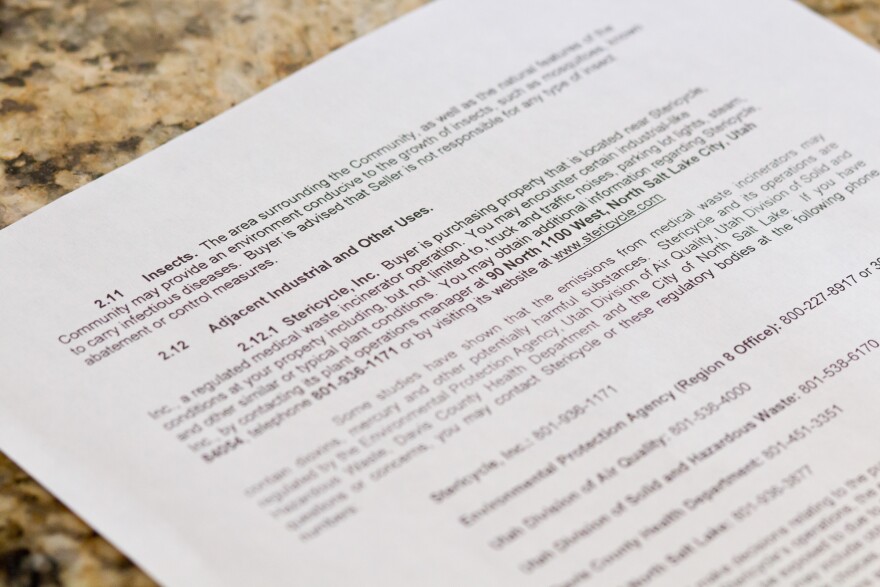

Looking back at the closing documents they signed when they bought their house, Becca and Dan were warned about truck and traffic noises, parking lot lights, and steam, but nothing about pollutants.

Stericycle’s corporate office did not respond to our request for an interview. In a statement, the company claims to be operating under the parameters of its permit.

Even if that’s the case, Dan and Becca say they don’t feel safe in their home.

“Had I known what was actually coming out of that thing. I would never have built a home right next to it," Dan says.

“We are moving,” adds Becca.

But moving might not be so easy. Dan happens to be a loan officer and is concerned about property values in the neighborhood.

"I’ve definitely seen a big increase in people wanting to sell their homes, and a lot of it because of Stericycle. It’s a very real possibility that values could be affected.”

We talked to a number of families who say they were not aware of what actually went on at the incinerator until after they bought their home. They all say that information may well have influenced their decision whether or not to buy.

The question is, how did thousands of people come to live near a medical waste incinerator?

That story begins in 1990 when a company called Browning Ferris Industries - or BFI - wanted to buy some land over on the west side of North Salt Lake to operate an incinerator. When city officials reviewed BFI’s permit, there were no residents within a mile of the facility. But even then, locals at the time were concerned about public safety and medical waste in their community.

We looked back at the planning commission meeting minutes. One resident asked what the restriction would be for building residential homes near the proposed plant. The Chair of the planning commission Jerald Seelos said, “residential plans would be rejected because they would not comply with the overall intent of the West District.”

Stericycle bought the incinerator in 1999. Fast forward to 2002 – city leaders amended the general plan and rezoned the land for residential development.

Some prominent families in Utah owned the land next to the incinerator, and wanted to develop it. They hired Bill Wright who worked as a consultant for a company called Sear Brown. Wright saw an opportunity.

“At that time the bulk of the land was vacant, and it was large in size," Wright says. "It was an opportunity to envision a future that was not just typical industrial development.”

They made a deal with developer Woodside Homes to build a mixed-use development. But in order for all of this to work, they needed city officials to rezone the land to build residential homes. As it happens, consultant Bill Wright was on the city’s planning commission. And you know who else was on the planning commission? The current mayor of North Salt Lake Len Arave. At the time, Arave was the Chief Financial Officer for Woodside Homes. We asked Mayor Arave if that was a conflict of interest.

“There were concerns on the council that there would be conflicts of interest," Arave says. "We all understood that. I had to recuse myself. I didn’t participate in any debate, discussions, and I was very careful to keep myself out of it.”

Bill Wright said the same thing. And neither of them voted on this rezone issue.

As far as we can see in the meeting minutes, Arave really did stay out of it. But in a May 2002 Planning Commission meeting, Bill Wright presented the initial plan for a mixed use community. In the presentation, he described it as a premier development with mixed income homes, some commercial businesses, and a wonderful view.

We asked Mayor Arave if he thought it was appropriate for Wright to advocate for his plan while also serving as a commissioner.

“It probably isn’t a decision I would have been made if I were him, but it’s not my job to criticize people. I hate to throw rocks because we all live in a glass house. If it were happening under my administration, it would be my job to try and make sure it was fixed."

We also asked him if, as mayor now, if that situation were happening, would you have something to say about it?

“Yeah, I think so. I realize people have to make a living, but I think at that point they should probably make a choice to serve on the planning commission or make a living doing that kind of stuff."

Wright says he believed in the plan amendment that was proposed, but doesn’t think he had any undue influence on its approval. He says there was a healthy debate on the proposal. Other commissioners we talked to said they made up their own minds, and were not influenced by Wright.

What about public safety concerns? Well, there were concerns about the noise from trucks and visual disturbances from lights. But not a word in the planning commission meeting minutes about air pollution in relation to Stericycle. All the city leaders we interviewed say they had no reason to suspect that the incinerator’s emissions would be unsafe. The State Division of Air Quality assured them that the company was in compliance with their permit.

There was really only one commissioner who had serious concerns - Jim Gramoll, president of a construction business close to Foxboro. Gramoll was worried that the residents would force the existing businesses out. In fact, there were a number of businesses in the area who objected to the rezone for this reason. Stericycle did not object, but Gramoll says it wasn’t hard to foresee that there would be problems with neighbors next to a medical waste incinerator.

“We did know what was going on at Stericycle, and the risk involved in that type of work," he says. "We certainly could have and should have been aware that there is a potential for problems.”

An Internet search shows that there were medical waste incinerators around the country at that time that were coming under intense public pressure to close in California, Missouri, and Arizona. But all of the city leaders we spoke to say they were not aware of these conflicts at the time.

"We did know what was going on at Stericycle, and the risk involved in that type of work. We certainly could have and should have been aware that there is a potential for problems." - Former Planning Commissioner Jim Gramoll

It took about six months from the time the idea was introduced to when the city leaders gave final approval of the re-zone. Gramoll’s term ended before a decision was made. Today, he says there is a lesson to be learned.

“We shouldn’t rush and push the development of those areas and make exceptions to good land planning just for the sake of making it profitable for an entity," he says. "Let’s do our homework. That’s the area we could have done a better job.”

City residents are watching their leaders closely to see how they handle this situation. Local elections are coming up, and residents like Dan Hubrich say Stericycle’s incinerator is their number one issue.

“It’s a big enough issue now, Erin Brockovich came out here," he says. "It’s gotten a lot of attention. Whoever is leading in the city, needs to have this at the forefront of their priorities.”

For more on how the city's leaders are planning to respond to the situation check out part two of our series, What's Burning in the Backyard.