Last of three parts

In the high-stakes fight against fentanyl-induced drug deaths, one remedy is fairly simple: blue and white strips of paper.

Fentanyl test strips work like a pregnancy test. One line shows up if there’s fentanyl in a solution. Two lines if there’s none.

“Fentanyl test strips are a very basic level of prevention,” said Erin Porter, a public health analyst who works for a program that targets drug trafficking in Oregon and Idaho.

Porter says Oregon health officials give out test strips so users can tell whether their drugs contain fentanyl.

“The test strips are really sensitive. So what we want people to do is just test the residue,” she said.

The strips aren’t perfect. Porter says fentanyl sticks together in pills and powders like chocolate chips in cookies. If you test a bit that isn’t touching fentanyl, there’s a chance a strip won’t test positive.

But she says people want to know what they’re using, and many avoid fentanyl. It’s not only deadly — users often need fentanyl again faster to avoid withdrawal.

“When someone is in the throes of substance use disorder, they're just trying to not be sick,” Porter said.

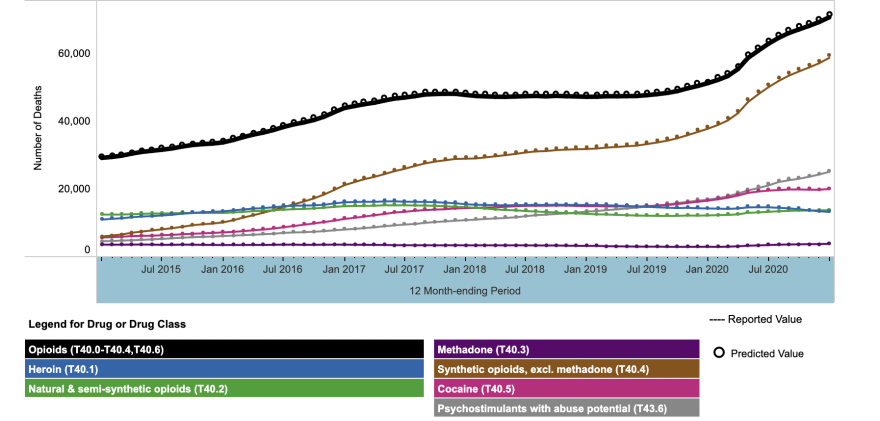

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates there were more than 90,000 overdose deaths in the U.S. last year — a record. And health experts say a big driver of that growth is synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

There are other efforts to avoid fentanyl deaths, too. Like increasing access to Naloxone, which can reverse opioid overdoses. Or decreasing stigma around addiction and improving access to addiction treatment.

But test strips are relatively low-cost and are easier to dole out than building new clinics or changing long-held stigmas. The strips can also change people’s behavior.

“Many of them took subsequent overdose prevention steps,” said Jacqueline Goldman, a project manager with the People, Place & Health Collective at the Brown University School of Public Health.

Goldman led a test strip study published in 2019. It showed that when young Rhode Island adults who used drugs had fentanyl test strips, they took precautions like avoiding drugs, using with other people and using slower.

That study had a relatively small sample of about 90 people. Now, Goldman is working on a larger clinical trial to give the federal government more guidance about test strips.

“We will be recruiting 500 people who use drugs who are between the ages of 18 and 65,” Goldman said.

In April, federal agencies including the CDC said states could use federal grant money to buy fentanyl test strips. But there’s a catch: fentanyl test strips are illegal in many Mountain West states, like New Mexico, Utah and Idaho.

Drug tests are included in their definition of illegal drug paraphernalia. Nevada only changed its paraphernalia laws this year to allow for fentanyl test strips.

Still, in Utah, health workers are giving the test strips out.

Utah Department of Health spokesman Tom Hudachko stated, “Technically they are illegal and clients using them could be cited; however, we have never heard of this happening and we worked with public safety before we implemented the test strip program. We hope to find a legislator to work with on clarifying the language in the statute.”

Fentanyl Data And Overdoses

But where are the test strips needed most? It’s hard to say with limited data.

The Mountain West was the last U.S. region to feel the brunt of the opioid epidemic or fentanyl products. Like many other black markets, it spread from cities and the coasts to more rural areas. But now fentanyl is here, and people are dying.

Chris Gibson directs the Oregon-Idaho High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area program.

These federally-funded programs are all over the U.S. They aim to reduce drug trafficking, increase inter-agency cooperation and provide training.

Gibson says his Oregon team has worked for decades on finding and aggregating data on overdoses and fentanyl. But states like Idaho and Montana have only had the last few years to start catching up.

“One of the things that our program did was it funded, and it is funding, an intelligence analyst in Idaho,” he said.

Once hired, that person would find and aggregate data around the state.

But Gibson says they need faster data everywhere, even Oregon. It should be as close to real-time as possible so officials know exactly where people are overdosing, when they’re dying and from what.

“The more proactive you can be in getting out in front of something, the more likelihood you're going to have … a positive impact,” he said.

So Gibson is promoting tools like OD map, which allows first responders to log overdose information after assisting a victim.

He says if authorities can at least track dangerous batches of drugs, states can work together to stop their spread and warn the public.

This is the third and final part of our series on fentanyl in the Mountain West.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2021 Boise State Public Radio News. To see more, visit Boise State Public Radio News.