Fifty years ago, two astronauts became the first humans to set foot on the moon. Like many explorers, they documented their accomplishment in photographs. The images they took are some of the most enduring of the 20th century, traveling from Life magazine to MTV to Twitter.

For most of us, the photos brought back by Apollo 11 are iconic and a little difficult to comprehend. But for astronauts, they represent something more: hours of training, risks taken and the many people on the ground who worked to make the journey possible.

NPR spoke to five former NASA astronauts who flew on space missions to learn how they see these photos. Their answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Training For The Mission

Leroy Chiao — Columbia, Endeavour, Discovery, International Space Station Expedition 10: I'm not even sure I've seen this [top] image before, but it's great because there's so much training that goes into a mission before you go fly it.

Wearing a spacesuit is not the most comfortable thing. You kind of have to learn to work with the suit rather than fight it. But it's still a very physical activity. You get bruises and hot spots and things like that. And it kind of gets to be a drag. It's not so exciting anymore. [All the training and studying is] good stuff, but it's just the sheer volume of it [that] starts wearing you down. That's actually one reason why astronauts decide they're ready to go do something else.

Lifting off

Russell "Rusty" Schweickart — Apollo 9: You've simulated it hundreds of times — if not a thousand times. So what you're anticipating is your role in doing an abort. If things are going normal, you're along for the ride until it puts you into orbit.

The main thing that you're feeling is, "For heaven's sake, don't let me screw up if something goes wrong."

Generally speaking, the ride itself is great. It's a surprisingly smooth and quiet ride.

The Lunar Module

Catherine "Cady" Coleman — Columbia, ISS Expedition 26/27: Wow, that was really them. They were on their way. Having the edge of the window in it just makes it real. In a more visceral way, you know that there are people on board there.

Schweickart: I mean, it's an ugly beast. But for us, it was beautiful. It was just incredible.

The People On The Ground

Mike Massimino — Columbia, Atlantis: [Mission control is] paying attention to every word. [An astronaut has] to be careful what you say. You might set off a chain reaction of things that you didn't intend just because you said, 'Hey, my boot feels a little tight.'

It's not like your mom watching you do your homework or someone looking over your shoulder to see if you screw up. They're with you. Your success is their success. Your failure — they take it as their failure. They have as much at stake in whatever you're doing as you do.

Coleman: There is a programmer named Margaret Hamilton who led the team that helped with the software to land on the moon. And she was responsible for figuring out the prioritization of alarms so that the system wouldn't just be clogged in alarms and unable to function.

Any astronaut is always going to tell you that it's a huge team that gets them to space. I see celebrating Apollo as an opportunity to help everybody understand that it's always been a diverse team, just not diverse enough.

One of the ways to make sure there is diversity in the future is to make sure that the people of now can see themselves in that past.

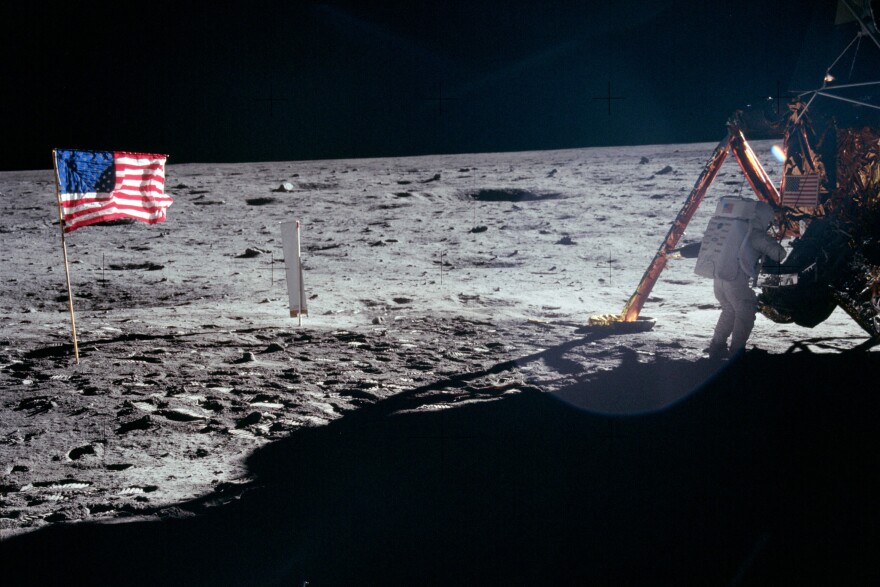

The First Moon Walk

Massimino: When I see this, I think of leaving the air lock to do a spacewalk. It's different once you actually get out there and experience it. For me, it was kind of like being at an aquarium, saying, "Look, there is all the pretty fish" versus being a scuba diver. You're no longer looking at the pretty fish in the aquarium — you're a scuba diver interacting with that environment. You really are a spaceman, or in this case, you are really becoming a moon man.

Returning To Earth

Charles Bolden — Columbia, Discovery, Atlantis: Your balance [on landing] was really messed up. And so you had to make an extra effort to make sure that you kept yourself vertical and you didn't turn your head or do anything else that might disorient you.

On any given day during the shuttle era, we might have someone who really had a difficult time getting down the ladder on their own. So, I can only imagine what it was like for [the Apollo 11 crew] to try to deal with bobbing up and down as if they were a cork and then getting into a life raft, waiting for a helicopter to come.

Coleman: You know they took a lot of risk.

It's almost out of respect for the others of their era that I try not to idolize them. But I certainly respect them for what they did, and I think it's hard to imagine in our program now how much more risk and unknown factors there were.

Seeing how easily they navigated those things, I would say that those three are so inspirational. It just reminds me that [being an astronaut is] a very special mantle to wear. I feel very privileged.

Looking Back At Earth

Bolden: The grandeur of Earth is just mesmerizing. You can distinctly see the horizon, this thin blue line going around kind of separating the Earth from the blackness of space. Those kinds of things are just overwhelming to the human eye and to the human psyche.

Chiao: It's still hard to believe that we did this 50 years ago.

Schweickart: These questions came kind of uninvited, just floating into my mind. Who am I? How did I get here? Why am I here? What's going on? You know, all of those questions that, when I sort of opened up to just being a human being in space and not an astronaut ... I didn't try to answer them.

Coleman: When I look at [this] Earthrise picture, one of my first thoughts is, "I am so glad that they took a picture." You know there's the mission itself. I mean, just to get there, accomplish the actual objective and get home safely is enough to ask of any human being.

If you don't bring back pictures like this one, people are not going to be able to feel what it was like to be there.

Massimino: I wish I was there with them.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.