Two wildfires burned over 13,600 acres in Washington County in July — ripping through protected Mojave Desert tortoise habitat.

And these aren’t the only fires that have scorched the area. In 2005, fires burned up a quarter of the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve, which is 62,000 acres of tortoise habitat set aside from development in booming Washington County.

Now, reserve and wildfire managers are grappling with what to do about frequent wildfires in an ecosystem that’s not adapted to them.

Just weeks after the fires were put out, biologist Mike Schijf walked over charred bushes and grasses. He was surveying the area for Mojave Desert tortoises, which are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

“Looking around it’s a patchwork of some tiny shrubs. I don’t even know if they’re dead or they’re alive, and other than that it’s kind of a moonscape out here,” said Schijf. He’s with the Washington County Habitat Conservation Plan, which helps manage the reserve.

Schijf looked for burrows by searching holes in the ground and openings among the red rocks. When he found a hole he thought a tortoise may be in, he held out his phone, reflecting sunlight into it. He could see a tortoise several feet back. This one didn’t seem to have any fire damage, likely because it sheltered in the burrow during the fires.

These burrows don’t just offer refuge for tortoises — they also shelter other desert animals like lizards, burrowing owls and rodents. Mojave Desert tortoises are considered keystone species because of the role they play in the ecosystem.

Normally, tortoises would stay deep underground for most of the day to escape the Southwest heat. Tortoises leave their burrows to get food and water, but the dry conditions this year haven’t given them much reason to leave their shade.

In more ideal conditions, a tortoise spends its day foraging for native plants, according to Sarah Thomas, with Conserve Southwest Utah.

“Tortoises get most of the water they need to survive from the plants that they eat because we know in the Mojave Desert there’s not a lot of free water sources,” Thomas said.

Tortoises have a “canteen-like bladder” that means they can go about a year before they need to drink water again, but Thomas said she’s worried about what will happen now that these plants have burned up.

Recent counts estimate that 2,000 adult tortoises live in the reserve, but that was before this year’s fires. The 2005 fire season directly killed 15% of the adult population in the most densely populated part of the reserve.

At a habitat conservation meeting in August, reserve managers estimated that one in four tortoises have died this year. But the summer heat makes it hard to find them, and it will take some time before they have exact numbers.

“We’re hopeful at least that most tortoises were in their burrows,” Schijf said. “But of course the long-term impacts of habitat loss are every bit as concerning.”

Unlike forested areas where fire is a natural part of the environment, in the Mojave Desert fires wipe out native plants and let cheatgrass take over. That invasive plant doesn’t offer the tortoise much nutrition, and Schijf said it can get lodged in their mouth and nostrils.

Cheatgrass also becomes a tinderbox, according to Clair Jolley, an assistant fire management officer for the Bureau of Land Management’s Color Country District.

“It all starts with a wet year, you get a bumper crop of cheatgrass, then you get a dry year that follows, kind of like we’re in now,” he said.

Jolley said historically wildfires happened every 200 to 300 years in the Mojave Desert. Now, they can happen every couple of years.

“It doesn’t take much, a flat tire … and a little bit of a breeze and it’s going to go because you have that grass that’s been hanging around for a year and it’s ready to go,” Jolley said.

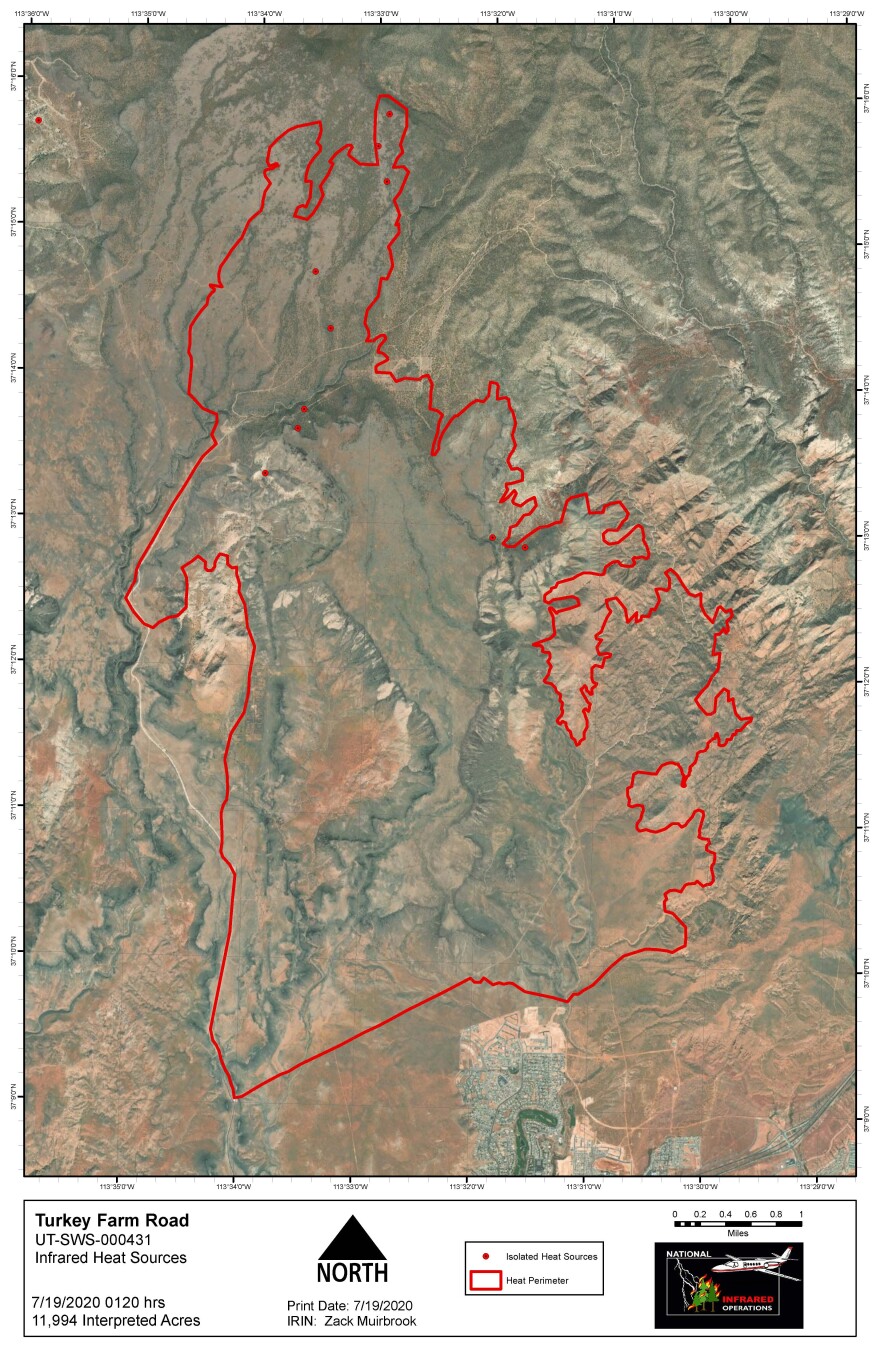

That’s what started the Cottonwood Trail fire in late July. I-15 runs along the reserve, and a blown tire on the highway ignited over 1,600 acres. The Turkey Farm Road Fire started a week earlier because of people lighting fireworks, which is prohibited on federal land. It burned almost 12,000 acres.

Across the state, human-caused fires account for 75% of this year’s season.

“If we can eliminate the human starts, it would go a long way to helping out the situation,” according to Keith Rigtrup, the BLM field manager in St. George.

Rigtrup said the agency has learned a lot about fighting fires since the devastating 2005 season. Then, firefighters were hesitant to drive across the landscape for fear of injuring individual tortoises.

“The thinking now has really changed to put it out. We do everything we can to contain it because the loss of habitat is more important than if, say, in your tactics you might injure or kill some tortoises,” Rigtrup said. “As unfortunate as it is, it’s better than having a big chunk of habitat burn off.”

In the wake of the fires in the reserve this year, Rigtrup said the BLM is working on seeding native plants and fighting fires more quickly in Red Cliffs. Rigtrup said the priority though remains human life and infrastructure.

For Mike Schijf, this year’s fires show the importance of prevention.

The reserve is a patchwork of federal, state, local and private land. And as climate change brings drier years and more wildfires to Utah’s southwest, Schijf said all of the management agencies need to work together to figure out ways to be more proactive.

“If things stay the way they are now, there’s no question this is going to keep happening,” Schijf said. “It’s a challenge that we’re going to be dealing with for years to come.”