The Native American Women Warriors Color Guard kicked off the White House Tribal Nation’s Summit late last year by carrying flags through an auditorium to traditional music. The procession symbolized the nation-to-nation spirit of the two-day event, which served as a venue for the Biden administration to announce a range of new commitments to Indian Country. But for all the progress the federal government has made recently, the summit made clear how much work remains in solving the persistent, intractable crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous people.

“Native American families and communities have endured persistently high levels of violence. Women and girls have borne the brunt of that violence,” said Attorney General Merrick Garland. “The crisis of missing or murdered Indigenous people has shattered the lives of victims, their families, and entire tribal communities. This is unacceptable.”

In 2021, more than 9,500 Indigenous people were reported missing through the FBI’s National Crime Information Center. That’s a higher rate of disappearance than the general U.S. population. Murder is also the third leading cause of death among Native women, according to the Urban Indian Health Institute.

Peter Yucupicio, chairman of the Pascua Yacqui Tribe in Arizona, said at the summit that each case affects communities in unimaginable ways.

“That hurts us as a people, as tribes, as women, as families,” he said. “You're destroying not only that family, but every single attachment to it.”

The issue has gotten more media attention recently, and officials have taken several actions to solve more cases. That includes the passage of Savannah’s Act, which directed the attorney general to review and revise protocols to address missing and murdered Indigenous people, and President Biden’s proclamation that May 5 is Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day.

Yucupicio said heightened attention on the issue is welcome because he’s been frustrated with law enforcement inaction for a long time.

“It took a while to understand why are they not picking these cases? Why are they not doing this and why is that person still on the streets and he's still walking, even though he hurt somebody?” Yucupicio said.

Yucupicio’s also been encouraged by the creation of a Missing and Murdered Unit within the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

But others say the rollout of federal solutions has been slow. Amber Torres, chair of the Walker River Paiute Tribe in Nevada, said at the summit that, for the dozens of tribes within her state’s borders, there’s access to just one special investigator. She stood up during the summit to challenge federal officials.

“We continue year after year to tell the same stories, but who's listening and what's being done about it?” she said. “We are not getting answers to the cases that are being submitted – waiting for even an email back.”

Ahead of the summit, the White House announced a number of actions to support tribal nations and address some shortcomings.

One issue is understaffing. Low pay and isolation on many tribal lands in the Mountain West means vacancies are hard to fill and employees are hard to keep. The Interior Department said it’s trying bonuses and other tools to hire and retain people, and they want to provide more resources for local tribes to maintain their staff.

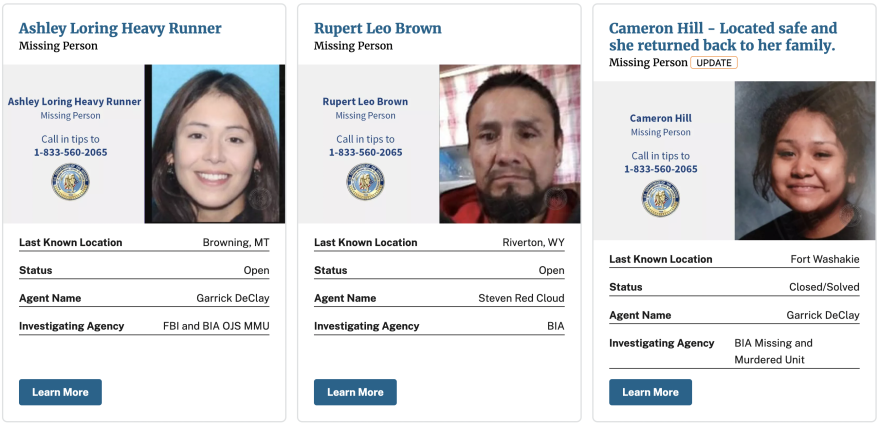

Data collection is also a persistent problem. The Bureau of Indian Affairs has a website that lists open missing and murdered Indigenous cases. As of Jan. 13, it only names 45 people. Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland said he knows that number is way too low. The website was launched in 2021, and his goal is to make it more comprehensive and useful.

“What are we trying to do over the next six months, it's to do better,” he said. “And be responsive when people call for help.”

The Justice Department is also hiring liaisons to improve coordination between tribal, state and federal law enforcement. The Albuquerque FBI Division recently released a more comprehensive list of open cases in New Mexico and the Navajo Nation, and the state has a response plan that includes creating resource guides for victims, as well as media awareness campaigns.

But Newland said jurisdictional confusion is often still one of the largest hurdles nationwide.

“At the outset of these cases, one of the first questions we have to ask is, who has the lead? And that question itself is complicated, and that makes it difficult to act with speed,” he said. “It makes it difficult to allocate resources, and that’s been a challenge.”

Meanwhile, over the past few years, several states in the Mountain West have begun their own initiatives to confront the epidemic. New Mexico, Wyoming and Utah have created task forces to look into solutions. Idaho’s legislature commissioned a report to investigate challenges and opportunities related to this issue.

Colorado also recently launched an Indigenous persons alert system in early January, which has already been put to use. Washington State has seen success when sending out widespread notifications. Wyoming has a bill on the table this legislative session that would expand its alert system to cover all at-risk missing adults.

Cara Chambers, director of Wyoming’s Division of Victim’s Services, said the crisis has its roots in centuries of mistreatment of Native Americans by colonial governments.

“There's quite a bit of reckoning with treatment of Indigenous people throughout our country's history and how that is not unrelated to how we got here,” she said.

She said recognition of that fact from states and the federal government, as well as investment toward vulnerable populations in tribal communities, would go a long way to reducing incidents of violence in Indian Country. Since becoming the first Native American Cabinet secretary in U.S. History, Deb Haaland has announced initiatives to investigate the legacy of federal boarding school policies, remove derogatory place names and improve the protection of Indigenous sacred sites.

“In victim’s services, it’s not always an encouraging field, but I am encouraged,” Chambers said.

Many Indigenous leaders also said at the Tribal Nation’s Summit that, while government help is necessary, maintaining tribal sovereignty is still critical. They want to give local law enforcement the space and training to prosecute and investigate crimes in culturally appropriate ways. That could give victims and their families the best chance to receive the help and closure they deserve.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2023 Wyoming Public Radio. To see more, visit Wyoming Public Radio.