La Niña is coming. For Utah’s ongoing water challenges, that could either be good or bad news.

This weather pattern is the cool phase of a climate cycle known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, when temperatures in the Pacific Ocean drop below normal. It doesn’t have a particularly strong connection to Utah’s weather compared to other parts of the U.S., such as places prone to hurricanes.

Still, it could help deliver a wetter monsoon season to southern Utah, which relies on that precipitation during the hot summer months. But that extra moisture may not last.

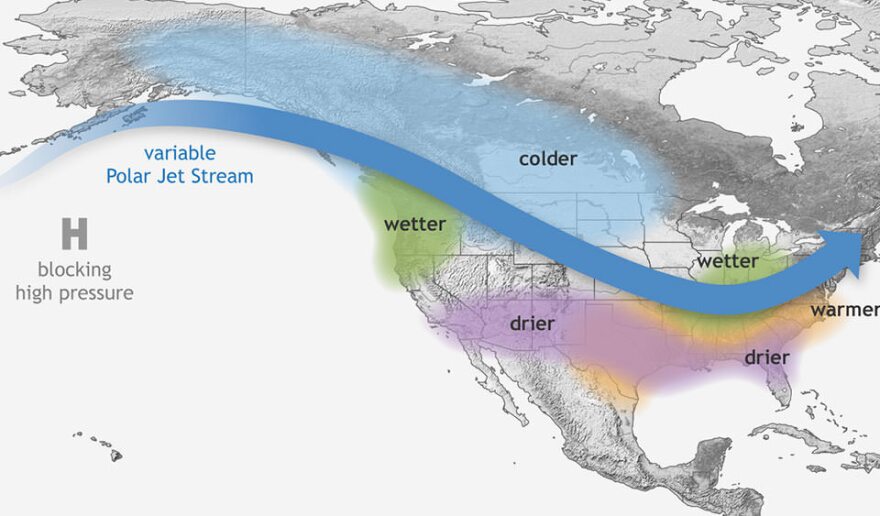

“As we get into the winter, one of the strong connections that La Niña has is drier and warmer conditions through the West and the South, which can lead to drought,” said Emily Becker, who writes about El Niño and La Niña for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The latest NOAA forecast predicts an 83% chance the current El Niño will end by June and a 62% chance La Niña will take its place between June and August.

The timing of La Niña’s arrival matters for Utah’s weather. If it doesn’t show up until the end of summer, it might be too late to have an impact on this year’s monsoons. But Jon Meyer, assistant state climatologist with the Utah Climate Center, said the outlook remains favorable.

“If we had to put money on any of those scenarios, the delayed onset and more active middle and late summer months for the monsoon is probably where I would put my chips right now.”

A wetter-than-average summer could be especially handy if the forecast for a drier winter comes to fruition. The chance of La Niña developing by December is more than 80%.

“Our desert Southwest neighbors California, Arizona and New Mexico tend to have drier [winter] conditions during these La Niña events. Southern Utah joins that, to a degree,” Meyer said. “We're a little bit less confident in how that will affect farther up into the Utah latitudes.”

There’s also a chance that it could pile on top of existing climate change and aridification, said Becker, who’s also associate director of the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies.

“The trend is already towards drier and warmer in the West. So La Niña can tilt the arms even farther. … Then you run the risk of compounding those effects.”

But drawing long-term weather forecasts from these patterns can be tricky.

Utah’s most recent La Niña winter in 2022-2023, for example, brought record-breaking snowpack instead of dry conditions. Things get even more unpredictable as climate change pushes the Earth’s weather into new territory, she said. Scientists are still figuring out how broad climate shifts, such as alarmingly warm ocean temperatures, impact patterns like La Niña.

Other times, however, the forecasts hold up. The current El Niño ended up being one of the five strongest since 1950, Becker said, and, as predicted, it brought some extra moisture to southern Utah this winter.

St. George received 3.57 inches of precipitation from December to February, ranking this meteorological winter as the 34th wettest out of 130 years on record. In Cedar City, 2.71 inches fell, making it the 25th wettest winter out of 76 years. Canyonlands National Park got 2.33 inches, its 11th wettest out of 58 years, and Bryce Canyon National Park got 5.10 inches, its 18th wettest out of 64 years.

“The problem, of course, is you can never point to any particular thing and say, ‘Well, that's El Niño, right there.’ But we do expect to see those patterns,” Becker said.

When it comes to winter precipitation, Utah shares an even stronger connection with another Pacific Ocean weather pattern, the quasi-decadal oscillation.

That trend also increased Utah’s chances for wet winters over the past few years, Meyer said, and likely combined with El Niño to create the eye-popping snowpack in 2023. In a winter where it and La Niña are pulling in opposite directions, however, it’s uncertain how the tug of war will play out.

Regardless, Meyer said it highlights the need for Utah to conserve precipitation when it gets it. Based on the quasi-decadal oscillation, the state may only have two or three more years before things dry up as they did in the early 2020s.

“That means hopefully we have a couple more years of building up our savings account in our reservoirs and our soil moisture and our groundwater. But for the back half of the 2020s, our expectation is that we'll be back in that dry phase. … That opens the door for those multi-year droughts.”