NASA has sent rovers to explore Mars before. But three words explain what makes this latest mission to Mars so different: location, location, location.

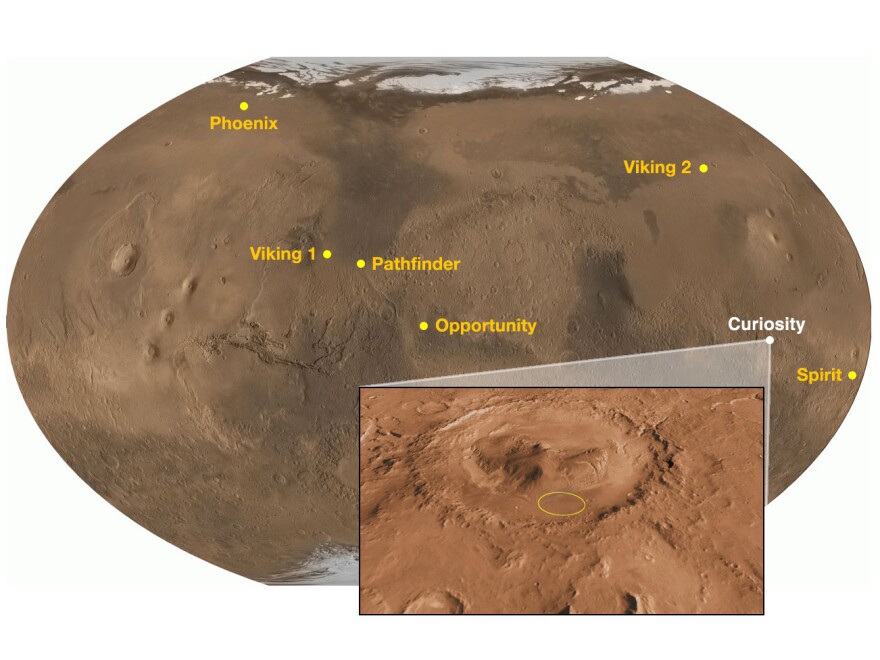

The rover Curiosity is slated to land late Sunday in Gale Crater, near the base of a 3-mile-high mountain with layers like the Grand Canyon. Scientists think those rocks could harbor secrets about the history of water — and life — on the Red Planet.

"It's got a giant mountain in the middle of the crater. There are lots of exposed layers [of clay and minerals]," says Samuel Kounaves, a chemistry professor at Tufts University who will analyze data from the mission. "Instruments aboard the orbiters have told us that a lot of the minerals in that area are minerals that would be formed with water present, so it's a very interesting area."

Water is essential for life on Earth, so where there's evidence of ancient water on Mars, researchers think they might also find clues to ancient life. "[Curiosity] is not going to be looking for life directly, but it's going to be looking for past habitability," Kounaves says. "We're looking to see if the elements required for life are there."

Curiosity carries 10 experiment stations. One, called Sample Analysis at Mars, or SAM, will use instruments like a mass spectrometer and gas chromatograph to look for elements that exist in the Martian soil and atmosphere. Scientists back on Earth will then calculate how those elements may have influenced the history of Mars, including the possibility of microbial life.

Geologist David Blake from NASA's Ames Research Center says rocks are a great place to look for clues because certain minerals form only under certain circumstances. "If we identify all the minerals that are present in, say, a 4-billion-year-old sample in Gale Crater, we can tell you what the conditions of the environment were; whether it was a lake, whether it was a stream-bed, just what the surrounding conditions were."

Blake is in charge of a chemistry and mineralogy instrument on the rover called CheMin. It is charged with identifying the minerals in a rock sample. Earlier expeditions have found minerals like olivine, which form in lava, and jarosite, which precipitates out of water. The minerals reflect the Mars environment at the time the rocks were formed.

"If you look for a billion-year-old rock on the Earth, you won't find it," Blake says. That's because Earth is still geologically active, and old rocks are being buried.

But on Mars, very old rocks are still sitting on the surface. "So we can go to Mars and look at rocks that are probably very similar to the early Earth and tell a story about both planets."

Scientists also will be evaluating the chemical composition of the Martian landscape using color photography.

"We use color as a way to understand, in a relatively simple sense, the geology and the composition and the mineral content of the rocks and soils there," says , a professor of astronomy and planetary science at Arizona State University who is working on the project.

"If we see a black rock, it's probably a fresh-from-Mars volcanic material, just like you'd find in Hawaii or Iceland," Bell says. This visual analysis, though not completely reliable, is a simple and energy-efficient way to classify the minerals seen in the Martian soil, he adds.

It's not all work and no play, however, for Curiosity's high-resolution cameras. "One of the things we do with these color cameras is the same thing that you or another tourist would do with their cellphone camera: Just look around and take beautiful color pictures, and soak up the landscape," Bell says.

Curiosity's landing will be a nail-biter; engineers had to devise a high-risk landing system that lowers Curiosity to the ground with cables from a hovering sky crane. (Check out our report on Adam Steltzner, the rocker who led the lander design effort.)

Tune in to see if it works at about 10:30 p.m. Sunday PDT; video from Mission Control (not from Mars) will be broadcast live. You can catch it in Times Square, too.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMzY5MzE4MDEzMTE3ODg5NDA4ZjRiNg004))