The Bureau of Land Management is moving more staff and—perhaps most significantly—its headquarters to the Mountain West.

Depending on who you ask, relocating the BLM’s headquarters from Washington, D.C. to Grand Junction, Colorado will make the agency more efficient, give preferential treatment to the fossil fuel industry—or even functionally dismantle it.

By the end of next year, 27 BLM staffers will likely move to the idyllic town halfway between Denver and Salt Lake City. And hundreds more will be scattered across the West.

Grand Junction Mayor Rick Taggart says the shake-up will give his city a stronger political voice.

“As a smaller city in western Colorado, we’re not as well-known,” Taggart said. “And because of that sometimes, we don’t have the voice even in our state government that we’d like to have.”

But it’s not just local voices expected to be amplified.

Jeremy Gelman, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Nevada, Reno, where he studies Congressional partisanship and agenda-setting, says industry also stands to benefit.

“In the case of the BLM, mining interests, logging companies, farmers, ranchers, their locus of power—their epicenter of where most of their people are—is out West,” Gelman said. “And Republicans want those folks [to have] easy access to BLM when regulations are being written.”

And some of those folks will be close, very close.

The Grand Junction headquarters will be in the same building as a corporate office for Chevron, a state oil and gas association, and Laramie Energy, an oil and gas producer. In a statement, a BLM spokesperson said any suggestion that the location was chosen to give select special interest groups unethical access is “flagrant and ironic.”

Gelman says it’s hard to know the intentions behind the decision, but overall, he says there’s no doubt the move will make it easier for industry interests to access BLM bureaucrats—and harder for national environmental groups who employ lobbyists in Washington.

“For really big stuff, you’re going to expect all the big players to show up,” Gelman said. “But for the smaller day-to-day stuff—who you’re hearing from, what’s important, what’s not important—that sort of access does matter. It’s not everything, but it does sort of tilt the playing field a little bit to who can get that face-to-face time.”

That’s a selling point for Utah Congressman Rob Bishop, the ranking Republican on the House Natural Resources Committee. He says moving the BLM to the West puts agents closer to the lands they manage and local interests.

“Having people on the ground who have the ability of making the final decision, not just having a job there locally, but also having the ability of making those decisions, that’s going to be a net plus. That’s going to benefit people,” Bishop said.

But it doesn’t appear that some BLM staffers stand to benefit. Many agency employees have expressed frustration over the move. As ProPublica recently reported, 11 BLM employees have already quit, with more resignations expected, despite a relocation incentive.

That has some Democrats and environmental groups worried, saying that losing these seasoned staffers could further strengthen the influence of the oil and gas industry. Bishop doesn’t buy that.

“Why could simply the gas and oil industry have more influence than, say, an environmental group that’s out there, or a cattle ranger that’s out there?” Bishop said, calling it “an argument you come up with to try and find some reason to stop a logical move from going forward.”

Arizona Democrat Raul Grijalva, chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, can’t see the logic.

“The rationale for it is hard to figure out,” he said. “In fact, I don’t think there is one”—other than, he added, “making sure that...the fossil fuel industry is taken care of above anything else.”

Grijalva says his committee hasn’t been given enough information on the types of jobs moving West, and he’s concerned about decision-making positions being so far away from Congress.

“The last thing you want is little fiefdoms in each state making their own decisions and doing their own procedures,” Grijalva said. “And I think that’s part of the intention—to allow a state that is all for extraction and nothing else to have the freedom to do that without any oversight by the federal government to the law and to other requirements.”

Grijalva says he’s prepared to issue subpoenas if the committee doesn’t get the information it’s looking for.

The House and Senate have both refused to provide funding for the move in the latest budget. But a Department of Interior spokesperson says the relocation is moving forward using funding previously approved by Congress.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUER in Salt Lake City, KUNR in Nevada and KRCC and KUNC in Colorado.

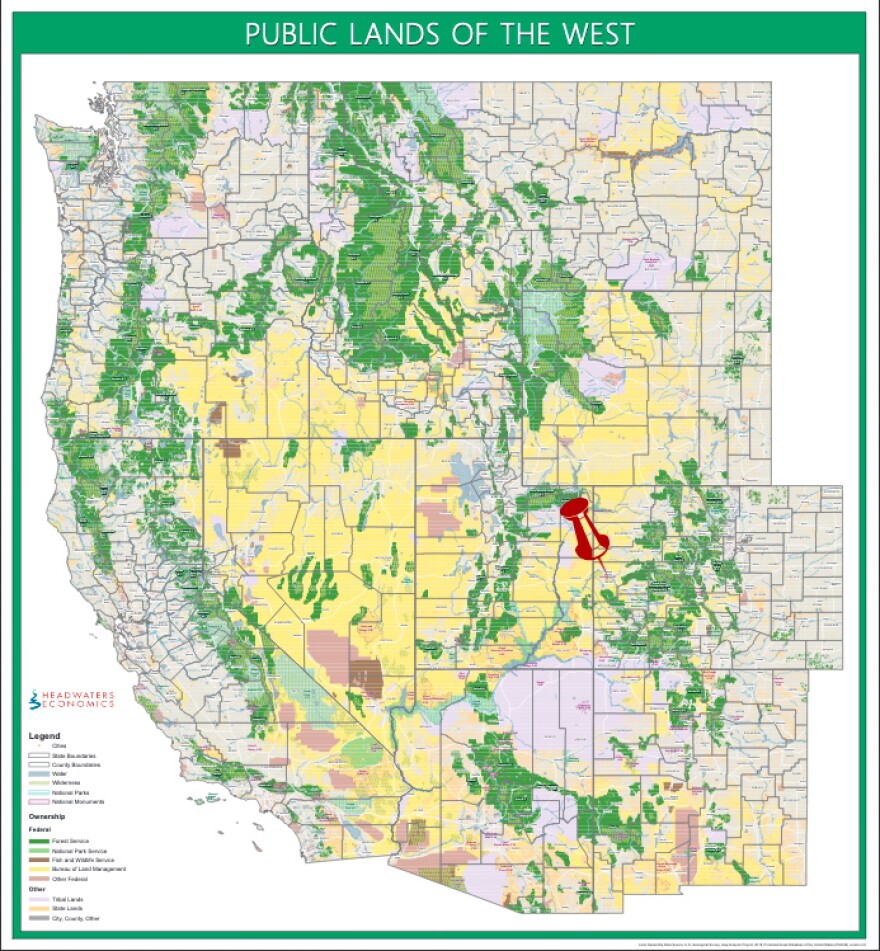

The public lands map used in this story comes from Headwaters Economics.

Copyright 2020 KUNR Public Radio. To see more, visit KUNR Public Radio. 9(MDAwMzY5MzE4MDEzMTE3ODg5NDA4ZjRiNg004))