Heidi Posnien’s turn-of-the-century farmhouse in Huntsville, Utah, and the nearby Shooting Star Saloon she owned and ran for more than two decades, are a far cry from her formative years in World War II Berlin.

Now, her story is being told in a book “A Child in Berlin,” written by Utah author Rhonda Lauritzen. Its release comes with the 80th anniversary of the end of the war.

Still, for 88-year-old Posnien it’s hard to talk about the past because of the memories.

“It took us five years to write this book,” she said. “It wasn't easy, and this is hard for me right now, to even talk about it.”

“But, I wanted to show people that no matter all the adversity, all the problems, you can still come out strong and healthy. You know, if you just put it behind you and live your life the best you can, that's what's important.”

The book begins in 1939 when Posnien and her opera-singing mother moved to Berlin. It was the same month Hitler invaded Poland.

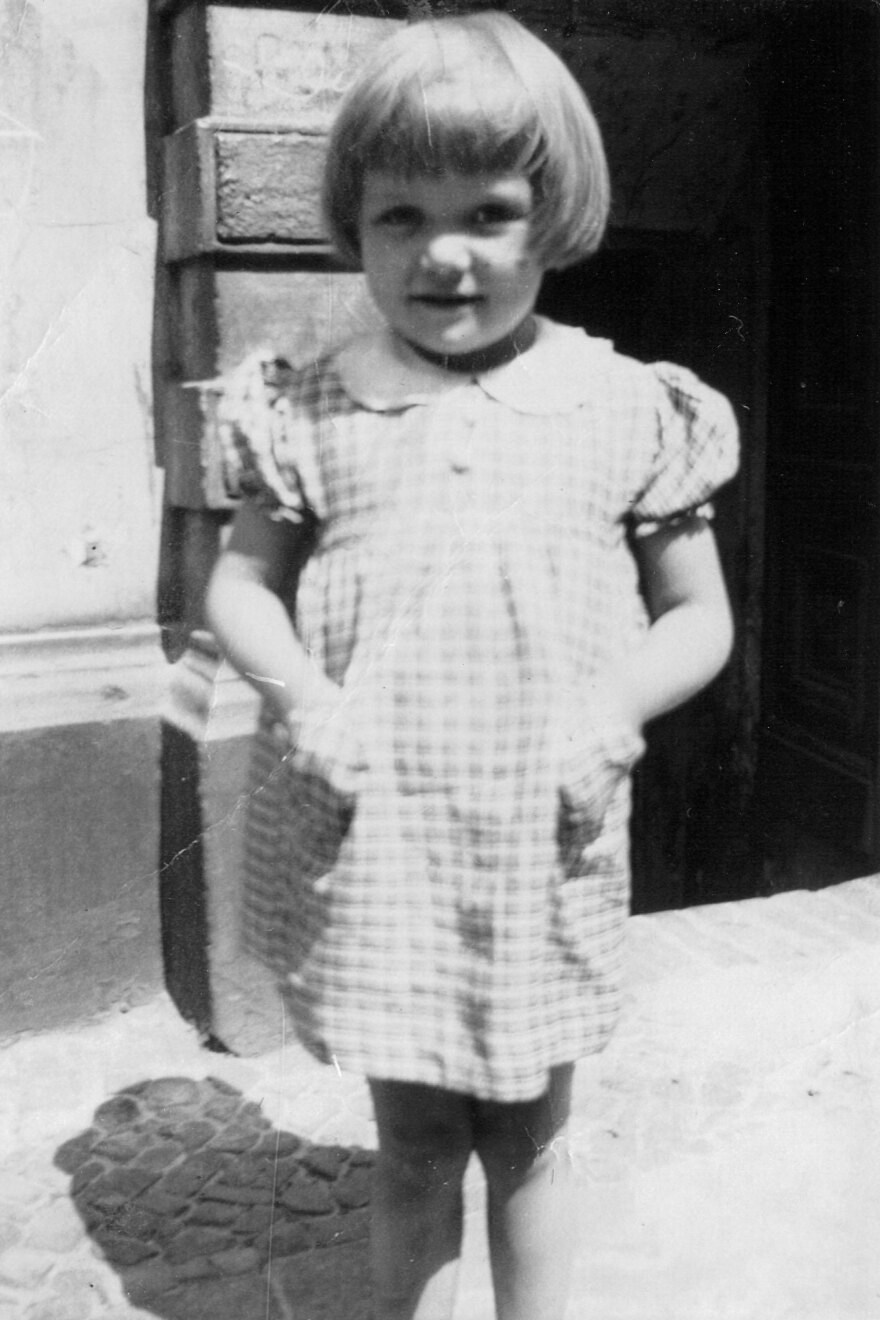

At the time, the Germans were looking for so-called pure Aryans to sing for opera-loving Berliners. And Posnien’s blonde, blue-eyed mother Käthe was a match.

Luaritzen said that even with the backdrop of a building war, Käthe considered it an honor to take up the offer, and she lived a heady existence — at first. She dated a Wehrmacht officer in the early days of the war and was once at a dinner party attended by Adolf Hitler. But things changed for her.

“Käthe began to see what was happening with her friends. Her best friend had a Jewish boyfriend; the Romanies who lived in her apartment building were hauled away. So terrible things were starting to happen around them. She had to choose between her dreams and her conscience, and she decided to leave the opera rather than join the party,” said Lauritzen.

Posnien witnessed it all through the eyes of a child.

“All of the sudden, there'd be these trucks coming up with Gestapo, and they would haul these people out of apartments and put them on the truck. I would ask my mother, ‘Where are they all going?’ She said, ‘They're taking them to the workhouses.’ All of our good friends and some of the children that I played with were disappearing.”

Posnien’s mother began to work in the black market to provide for them — until one day, the Gestapo came for her too, leaving the 9-year-old to fend for herself.

During one bombing raid, Posnien didn’t have time to make it to a shelter and watched her neighbors' homes burn — including one where a kind couple had often taken her in to comfort her.

“You could see how little by little, everything was burning, the table, the clock, the sofa where the husband would read stories to me. It was cold and there was glass all over my bed. I curled up and cried myself to sleep.”

Even with the bombings, Posnien said they did find ways to have fun amongst the rubble and ruins.

“In front of the house, there was an airplane wing and kids could stand on it and bounce up and down. This was just another game that we played.”

Hope that her mother would come back for her one day kept Posnien going in the darkest of days. Berlin, at the end of the war, was a city of women and children where the children basically had the run of the city while the mothers stood in the ration lines, said Lauritzen. To her, “A Child In Berlin” is Posnien’s story and a cautionary tale for modern times.

“They could not imagine that the concentration camps were real. The rumors were everywhere in Berlin, but today it’s called an imagination gap, because people heard it, but they couldn't believe that it was true. It was easier to believe that it was enemy propaganda.”

“So we must all be so careful, because evil will never sleep, and the minute that we think that we're past it and that it could never happen again, is when we're the most vulnerable. So, it's an important story for our day and it gives us pause about the decisions we make and the leaders that we follow.”

Poisnien, who was a child witness to what happened in Berlin, agrees.

“I don't know why they have to have war. Why can't we just all have peace and love each other, communicate with each other and be positive. In the book, I say eat life — don't let life eat you.”

Heidi Posnien and Rhonda Lauritzen will speak at The King’s English Bookshop in Salt Lake City on Jan. 29 from 6 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. The event is free, but registration is required.

On Feb. 22, they’ll give a free talk at the Weber County Library Pleasant Valley Branch from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m.