It's a Wednesday evening in December. Five o'clock means the end of my work day, and the start of Wampanoag language class.

"Wunee wunôq," my language teacher, Tracy Kelly, greets me as I join the Zoom call from my kitchen table in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

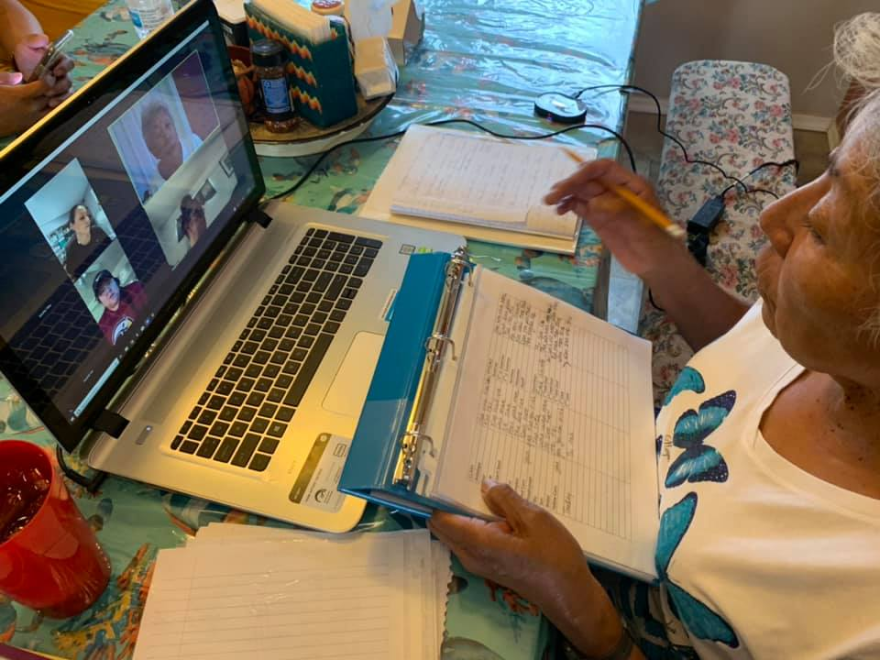

About 2,000 miles away in my hometown of Mashpee, Massachusetts, my grandmother logs on. My cousin Brooke and her two young sons' faces appear on the screen from West Virginia. Other students join from Virginia, New York and Boston.

After an opening prayer, we get to work. Twenty minutes of immersion smalltalk is followed by a grammar lesson and some deeply competitive vocabulary-learning games.

"I think I've got bingo!" Brett from Aquinnah announces after a particularly cutthroat round. To secure his win, he reads off the Wôpanâak words on his card.

"Wuneekun! Wunee anuhkôs8ôk," Kelly says in affirmation.

Like most Indigenous people in this country, I live away from my tribal community. My career has taken me west to Pueblo country, and it's not likely to bring me back home any time soon. Until recently, that meant I'd given up the opportunity to learn Wôpanâôt8âôk – the Wampanoag language.

"I didn't realize how many students want to come [to language class] and couldn't. They literally could not come because they lived too far away," Kelly told me in an interview recently.

She's a linguist with MIT's Indigenous Language Initiative, and an instructor with the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project. Historically, she said Wôpanâak language-learning has been deeply rooted in our homelands of southeastern Massachusetts. She said many tribal members struggle to make it to classes offered in only a handful of locations, and that she's long dreamed of making Wôpanâôt8âôk more accessible.

"But there wasn't complete community buy-in," Kelly said. "People get nervous when you talk about putting our language on the internet. It's like, 'Oh my gosh, who's gonna get it? Who's gonna see it?' And those fears come from a real place of being colonized and being exploited."

So, she kept some ideas in her back pocket until last spring, when the pandemic hit.

"It was kind of the perfect green light. It was like 'Okay, you're on. Good thing you've been working on this because we need stuff now,'" Kelly said.

Kelly built a secure language learning website called Kun8seeh, which means "Talk to me" in Wampanoag. It's only for tribal citizens and their family members. Kelly manually approves each user request, and uses the site to guide and supplement virtual language classes.

"Teaching on Zoom has definitely presented its bit of challenges, such as sort of an awkward flow at first," Kelly said. But she's developed strategies for keeping classes efficient and engaging. "You know, it's just a whole different way of relating to people and building community online."

Overcoming the digital divide

Christine Sims, a citizen of the Acoma Pueblo, directs the American Indian Language Policy Research and Teacher Training Center at the University of New Mexico. She says Kelly is far from the only language teacher facing these challenges.

"The learning curve for using these technologies can be very high for instructors," Sims said, adding that young Indigenous language teachers like Kelly are the exception to the rule. "Most Native fluent speakers are elders. Some of them may have never used a computer or the internet to teach."

And while Zoom-based classes might benefit urban and far-flung tribal citizens, Sims said that "technology inequities," especially a lack of broadband, could prevent those who live on rural reservations from participating. Rather than move online, Sims said some Indigenous language programs have stopped offering classes during the pandemic.

"Most programs are trying to utilize the internet to some extent, but it doesn't really always work out for all communities," Sims said.

Robert Hall coordinates Blackfoot language instruction at Browning Public Schools and teaches community classes on the Blackfeet Nation in Montana. He said trying to reach students during the pandemic has been "a puzzle."

"We live in a place of a lot of poverty," he said. "A lot of people just don't have the technology suitable for online learning," whether it's a lack of broadband access or of a device to get online.

So, Hall hosts a Blackfoot language program on Thunder Radio, which broadcasts on the Blackfeet Nation.

"I talk about Blackfoot words. I always share a prayer, because people love that. I'll even read from Blackfoot books and tell stories," Hall said. "If you can't access the internet from Browning, it's very likely you can access our radio station."

In order to cast an even wider net, he often streams the show live on YouTube and posts video lessons on the site, featuring a cast of puppet characters who sing songs and tell stories in Blackfoot.

"It's important to admit and accept that we need [language learning] to be entertaining," Hall said. "On a Saturday morning, kids aren't going to watch a video of their teacher talking to them. But they will watch a puppet."

Hall's videos – including an elaborate Christmas sing-along special – have travelled far beyond his rez, to Blackfeet people across the U.S. and Canada.

"I'm very unapologetically rez-centric," Hall said. "But with that being said, just because you're not growing up on the rez doesn't mean you ought not have access to our knowledge."

'Opportunity to carry on culture'

Minja Gaines and her daughter Deniale Urbina are grateful their tribe has adopted Hall's sentiment. They are citizens of the Acoma Pueblo, an hour west of Albuquerque, but they live in Virginia and Georgia, respectively.

"I think my mom was the one who saw the language class and I was like, 'We have to do this,'" Urbina said.

The virtual class, hosted by the Acoma Learning Center and taught by Marietta Jaunico last fall, was the first real opportunity for both women to learn their language. Although Gaines grew up in her tribal community, her older relatives rarely spoke to her in Acoma.

"I grew up hearing it sometimes, but my mother and aunts had gone to boarding school. They weren't allowed to speak their language at the boarding school, so some of it got lost," Gaines said.

In that way, Gaines and Urbina say the class helped break a generational cycle of cultural dispossession.

"I felt more like I knew who I was after [the class]," said Gaines. "It's something that I can hang onto now. It's mine."

Her daughter agrees.

"I think it means everything," Urbina said. "It gives me the opportunity to carry on culture that maybe I wouldn't be able to just because of the lack of proximity."

Gaines and Urbina are also conscious that the shift to video conferencing has had the opposite impact on some rural language learners. Once the pandemic subsides, they hope that both in-person and online learning can continue.

According to Christine Sims, that's the direction some Indigenous language programs are moving in.

"Some of the consequences [of the pandemic] have been positive in terms of connecting people that might not have been able to come together before," Sims said. "When this pandemic passes, whenever that is, you want to make sure that you build on those connections."

As for my language, Tracy Kelly said Wôpanâôt8âôk is only going to get more accessible.

"This has just been a first try, and I think it was a really solid try," Kelly said. "I've been praying about this for years – please send us a Wampanoag person who is passionate about technology. Because I would love to see video games, computer games in the language, apps like you would see on a kid's tablet. Let's have those in Wampanoag. I'm envisioning taking this way farther."

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, the O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West in Montana, KUNC in Colorado, KUNM in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2021 KUNM. To see more, visit KUNM.