After the state Legislature largely rolled back a law aimed at moving Utah away from cash bail reform, Representatives from Utah’s criminal justice system are back at the table to try to find a police they can all agree with.

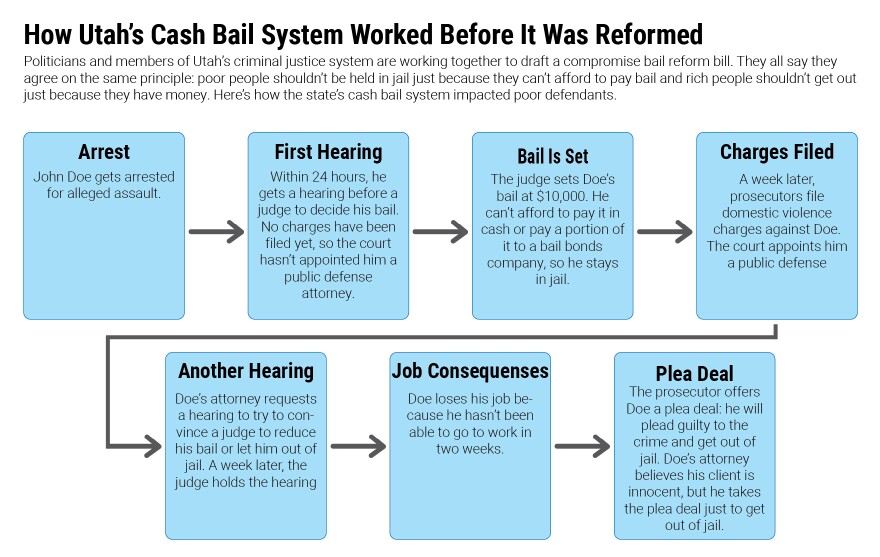

Members of the current working group said they still agree with the same underlying principle the original bail reform law was based on: poor people shouldn’t be held in jail just because they can’t afford to pay bail and rich people shouldn’t get out just because they have money.

To understand how staying in jail can wreak havoc on poor defendants’ lives, Utah County public defender Ben Aldana explained a case he might get.

“I'm going to give a hypothetical based on a type of offense that's always very contentious and factually, there's no way to figure out what actually happened,” Aldana said.

Let’s call his client John Doe. He’s been arrested for alleged domestic violence. Within 24 hours, Doe has a bail hearing.

“The bail would typically have been between $5,000 and $10,000,” Aldana said. “In my client's circumstance, with no money, they're stuck in jail.”

After a week in jail, Doe loses his job because he hasn’t been able to show up for work and he has kids to take care of. When the prosecutor offers Doe a plea deal for a crime Aldana said he’s not guilty of, he accepts it just to get out of jail.

That wouldn’t have happened if Doe could afford to post bail.

This type of inequity is exactly what lawmakers and members of the criminal justice system want to fix. They just don’t agree on the best strategy yet.

For example, some say the state should require judges to impose the “least restrictive” conditions before a trial. While others argue the law should use a different term to prevent judges from releasing dangerous people. There’s also a debate about how judges should use monetary bail.

“What's the fairest way to protect constitutional rights of those accused but not yet convicted and presumption of innocence — and public safety?” said Davis County Attorney Troy Rawlings. “That's what we're trying to get to in Utah.”