Just after 7 a.m. on Friday, 50 runners began to circle a fenced-in exercise yard in Salt Lake City. It was cool and cloudy with a light breeze off of the Great Salt Lake, an unusual break in the Utah summer heat.

After two years of organizing, this is the first half-marathon put on by Fit From Within. It took place entirely within the walls of the Utah State Correctional Facility.

Most of the participants wore prison-issued gray shorts and white sneakers. A handful of other runners, like Republican state Rep. Katy Hall, wore casual t-shirts and racing gear.

“They’re just people,” she said. “These could be your neighbors, these could be your kids, your parents, anybody that's in here. And we want them to be able to get out of here and be a part of society again.”

Hall got involved with Fit From Within in 2024 after watching the documentary “26.2 to Life,” about a running club at San Quentin Prison in California.

At the same time Hall approached prison leadership about creating a club, Casey Vanderhoef, an inmate, was getting a group off the ground. Vanderhoef had been inspired by the same documentary.

“I thought, man, we could do that here,” he said. “We have the facility. We have the willingness of staff.”

Now, state lawmakers work — and run — with the incarcerated athletes. Hall collects donations for sneakers and wants to raise funds for a set of new treadmills so that inmates can train indoors.

The club has an annual goal of 1,000 collective miles, Vanderhoef explained. Members train independently, but get the chance to run longer races as a group.

Many had zero running experience prior to joining. Some runners had white hair; many walked a portion of the race. Two completed their laps from wheelchairs. All finished.

Later this year, the organization will host a full marathon.

“It's just another way to feel seen, feel loved, as we work to make sure we return men back to their families in a better state than when they came in,” Vanderhoef said.

Not everyone who ran the half-marathon will return home. Some inmates in the club are convicted of non-violent crimes, while others are in for life or even on death row.

Usually, activities at the prison are determined by an inmate’s housing unit. That’s what makes Fit From Within so unique, Vanderhoef said.

The race took place in a lower-security unit. Inmates there get the chance to participate in programs like “Successful Offenders Learning Individual Development,” which prioritizes peer mediation, inmate leadership, and equitable relationships between officers and inmates.

In other high-security units, some individuals get just an hour of outdoor time a day. But Fit from Within brings together men from across the facility.

For Annie Snyder, a therapist at the prison, the facility-wide program is unprecedented and groundbreaking.

“We're combining people that maybe would never get together as it is,” she said. “It's a really great experience and opportunity for them.”

Snyder, alongside recreational therapist Ellie Madenberg, has been conducting surveys on inmate mental health after running.

“We actually have data to prove that running is decreasing stress, depression and anxiety in their lives, and this is benefiting them, and it gives them a sense of purpose, something to do, a group to be a part of,” Sydner said.

Beyond an inmate’s physical health, Vanderhoef said running transforms prison culture, especially for those with longer sentences.

“I have a really good friend who said something to me the other day. He said, ‘I have life without parole, not life without purpose,’" Vanderhoef said. “And I'm a big believer that men can find purpose wherever they're at and men do that in here as well.”

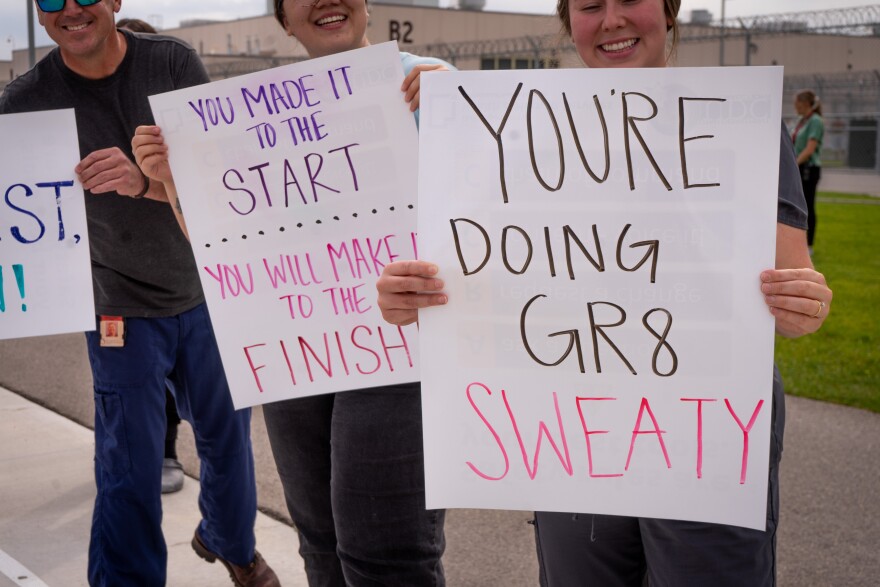

Prison employees and inmates cheered side-by-side, waving handmade signs. As they completed their 39th and final lap around the track, incarcerated and civilian runners called out to each other by name, shook hands and hugged at the finish line.

Vanderhoef was the first to cross it.

“We feel very seen,” he said. “I mean, I just got done running laps with state legislators. Sometimes when we're in prison, society feels very far away. And then we have events like this. We feel the love and we know we have people out there cheering for us.”

Vanderhoef is set to be released on parole the week after the race. With his winning time of 1:37, he said he hopes to qualify for the Boston Marathon.

Most inmates who return home after being incarcerated won’t make it that far. But it doesn’t mean they’ll stop running.

“There's a lot of people I've talked to that have gotten out already,” said Hall, “and they're like, ‘we want to come back and run the marathon in November.’”

The athletes, inside and outside of the facility, will keep training to get there.