When the Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1966, it was a major development for water management in the arid west. It would also transform Glen Canyon, sometimes described as America's “lost national park,” into the second largest man-made reservoir in the country.

On June 22, 1980, Lake Powell reached its capacity for the first time, marking a grim milestone for environmentalists who have never forgotten the loss of Glen Canyon. Before the waters began pouring in, it was a maze of towering sandstone cliffs and spires, with thousands of indigenous ruins now mostly lost.

Rich Ingebretsen saw it for the first time on a boy scout trip in the early 1970s, as the water was just beginning to rise.

“I have a vivid memory of that hike,” Ingebretsen said. “It was long and hot, just going up over boulders and cliffs. You'd walk up to a pool and slide down to the next lower one.”

He said he’s never forgotten what he saw, like when he was walking alongside the river and staring up at a wall of red rock. His scoutmaster pointed up to a mark near the top, hundreds of feet above them, and told him one day it would be underwater.

“I mean it was way up there,” he said. “And I just thought ‘that is unbelievable that there'll be that much water here.’ It made me sad to look at those cliffs and think that we'd never see them again.”

He said that sadness he felt as a kid — which would later morph into anger — also never went away. Ingebretsen would go on to dedicate his life to the canyon. In the mid-90s he started the Glen Canyon Institute, which has long advocated for draining Lake Powell and restoring the canyon.

It’s a feeling many activists share.

“That's one of the reasons it becomes such a lightning rod,” said Sara Dant, a history professor at Weber State University. “It's like the girl who got away. You just never get quite over that. And many environmentalists have never gotten over that.”

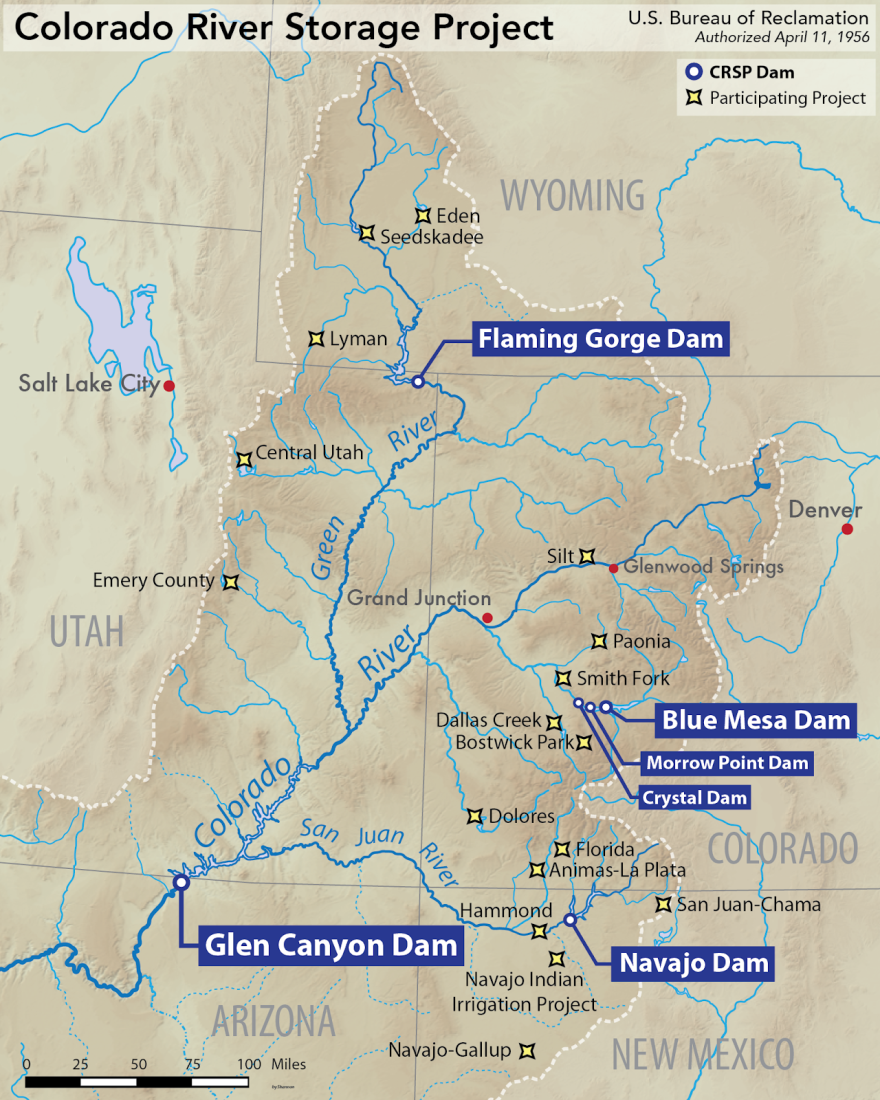

The Glen Canyon Dam was the biggest in the Colorado River Storage Project, a series of dams built to manage the notoriously unpredictable river — the most important water source in the west. Proponents of the project said it was not only critical to maintaining the west’s water supply through drought — it would also provide cheap hydroelectric power to states in the region.

An earlier proposal had aimed to build a dam in Echo Park in Dinosaur National Monument. But the environmental community mounted a major campaign to prevent it. Dant said influential people spoke out against the plan — there were magazine articles and a famous coffee table book by Wallace Stegner.

“It really electrified the environmental community, not just in Utah but across the country,” Dant said. “It was seen as a test case for the sanctity of the national park system.”

The campaign proved successful, and that dam was never built. But Dant said that in saving Echo Park, environmentalists agreed to allow the project’s other dams to go ahead unopposed — including one in Glen Canyon, which at the time was virtually unknown.

“It was remote. Nobody had been there,” she said. “Then they discover it’s stunning. And that was a real screw up.”

Led by the Sierra Club, environmentalists launched another campaign to save Glen Canyon, using tactics similar to those in the fight against Echo Park. But they were too late. By 1966, construction on the dam was finished.

Dant said the failure to stop the Glen Canyon Dam became a key marker for environmentalists in the country. It energized the movement, which, like the Civil Rights movement and protests against the Vietnam War, had begun to move in a more radical direction.

The dam played a central role, for instance, in Edward Abbey’s influential novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, about a group of eco-warriors who set out to sabotage and destroy industrial development in the American Southwest.

“I think we're morally justified to resort to whatever means are necessary in order to defend our land from destruction,” Abbey said of the philosophy in The Cracking of the Glen Canyon Dam. The short documentary depicts one of the first major stunts by the radical environmentalist group Earth First!, whose founders had been inspired by Abbey’s writings. In 1981, they rolled a giant plastic tarp down the side of the dam to symbolize a crack.

“The main reason for Earth First! is to create a broader spectrum within the environmental community, a wing that would make the Sierra Club look moderate,” said the group’s founder Dave Foreman, also in the film. “Somebody has to say what needs to be said and do what needs to be done and take the kind of strong action such as hanging a crack on Glen Canyon Dam to dramatize it.”

Dant said that for many environmentalists, Glen Canyon became a symbol of American hubris. It was one of the last major industrial developments of the era before environmental impact studies, when projects could move forward without considering the surrounding ecosystem.

“There had been this assumption for so long that development is good,” she said. “We had built dams because they were good for America. We got cheap hydropower and that enabled us to develop.”

By the middle of the century, however, Dant said people were beginning to see some of the unintended side effects of that expansion, such as the loss of Glen Canyon.

Still, the legacy of the dam and Lake Powell are complicated, she said. Because for all those who argue it should be drained and the canyon restored, many others say it remains a critical resource for managing water and generating power in the west.

And both, she said, are right.

In the second part of our look at Lake Powell’s 40th anniversary, KUER’s Lexi Peery looks at the role the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area’s role in the economy of Southern Utah and what climate change could hold in store over the coming decades for the reservoir.

Jon Reed is a reporter for KUER. Follow him on Twitter @reedathonjon