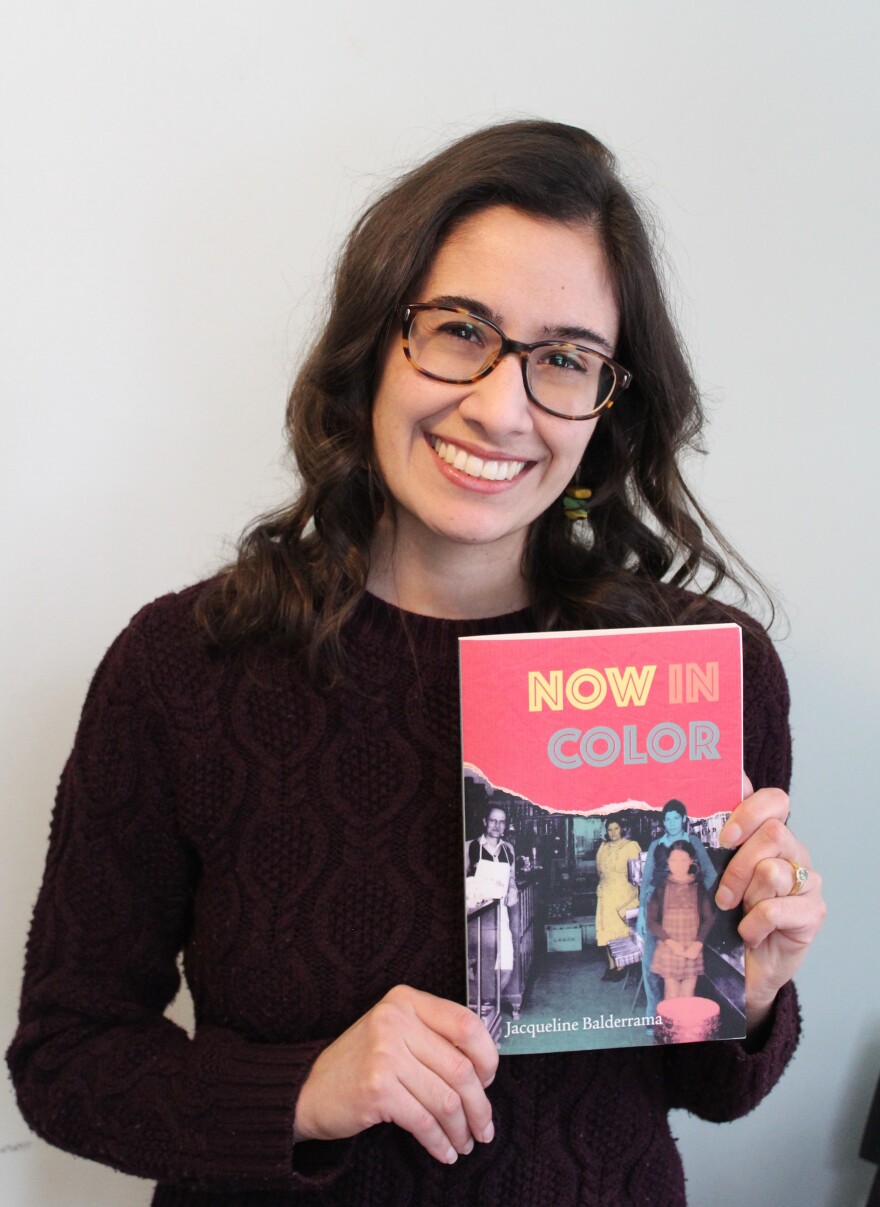

What makes up a person’s identity? That’s a question Utah-based poet Jacqueline Balderrama wrestles with in her recent poetry collection “Now In Color.” It’s a meditation on her own family’s history and her Latina identity.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Caroline Ballard: How did this collection come about?

Jacqueline Balderrama: I began writing this book roughly the time I was moving to Arizona for my MFA at Arizona State [University]. I was thinking a lot about my relationship to language and not being a native speaker.

CB: A native Spanish speaker ...

JB: Right, a native Spanish speaker. My native language is English. So I was confronting those feelings of what I should be and also accepting what I am. Language was one way to approach that.

CB: This collection is as much a family history as anything. You detail the story of your great grandfather who came to America from Mexico a century ago and of the experiences of generations since then. What can poetry say differently about your family's story than something like a memoir or a biography?

JB: I think poetry has the power to really zoom in on certain moments and fill a memory, but also acknowledge the fragmentation that's there. A lot of this history is lost to me. I have some access through stories I've gotten from my grandparents and parents. So poetry, I think, does a really interesting job of providing a medium to sort of fill in those gaps with interesting ways of thinking around the stories that are fragmented. So a lot of the poems involve some level of 'I've been told this' and also imaginings that sort of take you through time, through my current experience of my culture or lack thereof.

CB: Explain that to me — “culture or lack thereof.” What do you mean by that?

JB: I grew up in a mixed ethnicity household. My mother's white, my dad is Mexican-American. And so it's interesting to think what makes up a culture and what makes up an identity. I've been exposed to certain elements of Hispanic and Latino culture through cooking, but not through language. So there's like an element there that I do have access to, and there's also an element that I don't have.

CB: Could you read a bit of your poem, “The Queen of Technicolor, 1943” for us?

JB: I'd be happy to.

My grandmother's family changes the spelling of their last name to match: Móntes to Montez. Mountains to mountains. Part of the giantess exists in her.

And it's true. It's Celia Montez, like the movie star. Montez, The Queen of Technicolor, is always in love, or in the moment right before being in love.

CB: Tell me more about the grandmother in this poem.

JB: My grandmother is still alive. She's, I think, 94, 93 right now. And this was a movie star in the 1940s. Maria Montez from the Dominican Republic starred in these sort of exotic adventure films. So my grandmother would have been a teenager at the time. This poem sort of came out of a little, I don't know— hint of a story. She's suffering from Alzheimer's right now, so in a way, a lot of that history is lost to me. But knowing the fact that her family changed the spelling of their last name and thus the pronunciation, I think was really interesting to think about the importance of seeing representation on film. Even though she was this exoticized actress, I think it's really interesting to see that attraction and sense of belonging I think my grandmother felt to say "My name is like the movie star's."

CB: More broadly, how has writing these poems changed how you think about your identity as a Latina woman and where you fit into your family's history?

JB: I think the book, in a way, gave me language for speaking about my identity and confidence about sharing where I come from. I also had the experience while writing this with Letras Latinas, which is a program with the University of Notre Dame. They were doing this collaboration with Arizona State [University] where Latina and Latino writers joined from MFA programs to share their stories and form this community. From that experience, I gained a lot of confidence in just acknowledging who I am and that that's OK. And to recognize that there isn't a set definition that makes you Latina or Latino, there's a lot of variability within that — some Spanish speaking, some not. Writing this book, in a way, was coming to terms with that, as well.