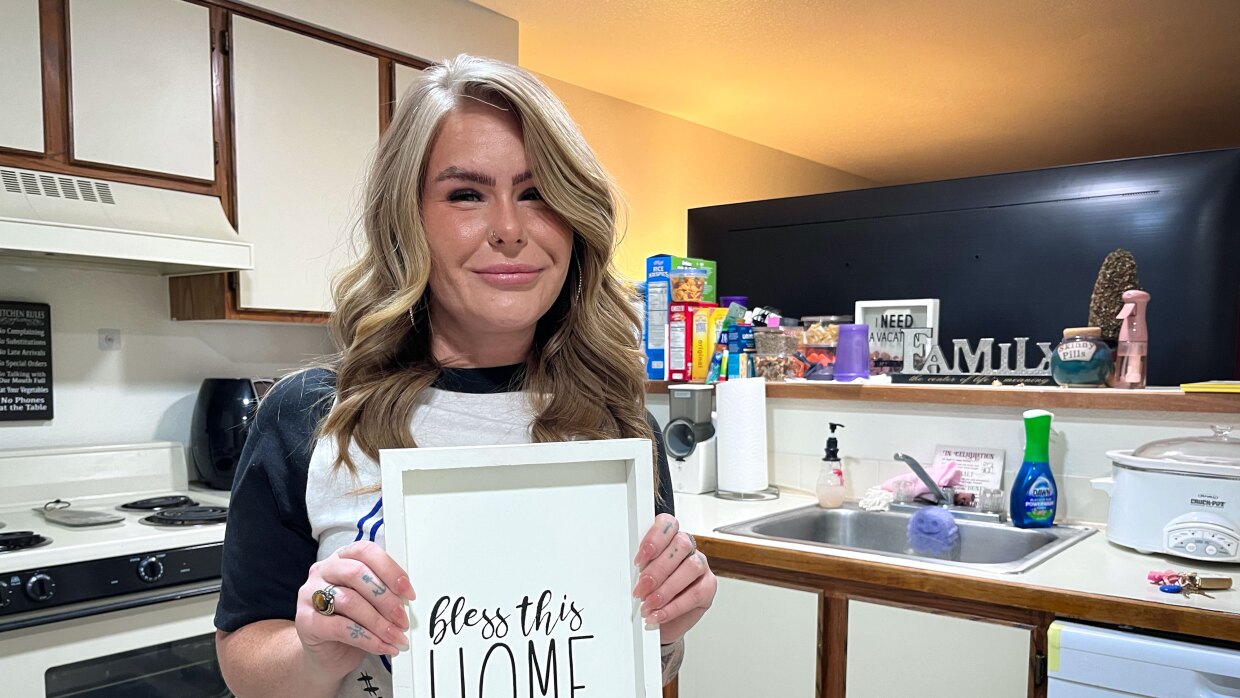

Skye Stucki’s studio apartment in St. George may be small, but she loves it.

The comfy couch. The elephant shower curtain. The long kitchen counter. The one dotted with ingredients for her first attempt at homemade bread.

But above all, Stucki loves finally having a place to call home.

This apartment became the first place she’d ever had on her own last year. It took a lot of work to make it happen.

“Trying to find a house with not the perfect credit is really hard,” Stucki said. “So when I got in here, I was so relieved, because I just didn't feel like it was ever gonna happen for me.”

The biggest reason was her budget. She works at a local supermarket and needs a place that costs less than $1,000 a month. That’s a vanishing target in St. George and many other Utah communities as the state’s affordable housing crisis pushes prices sky high.

A decade ago, the median rent for a studio apartment in Washington County was less than $600. It’s now over $1,300. Put another way, you could rent a three-bedroom apartment in 2015 for less money than the average studio goes for today.

So, Stucki had to make some hard choices. She decided not to pay for home internet and instead relied on her phone. She bought a used car with cash. She canceled some streaming subscriptions, too.

“I just don't buy anything that's not something that I need to breathe, live and survive,” Stucki said.

She also received temporary rental assistance through Switchpoint, a local homelessness and poverty services organization. One of their programs paid a diminishing portion of Stucki’s rent during her first year in the apartment.

Switchpoint CEO Carol Hollowell said she seen more and more people seek help as they get squeezed out of the housing market, both in St. George and at the organization’s locations in Salt Lake, Tooele and Davis counties.

“We're talking families, students, single adults who are working two jobs already, people on fixed incomes, people on disability,” Hollowell said. “Because their income is not increasing, either.”

Since 2015, rising rents in Washington County have outpaced income growth by more than 50 percentage points.

These dynamics make it hard for people budgeting to buy a home, too.

At her desk at the Washington County Board of Realtors, CEO Emily Merkley flipped through a blast from the past. It’s a 1991 real estate magazine filled with two- and three-bedroom houses for sale.

“Great location. Right in St. George. $49,900,” Merkley said, reading the details of one listing. “It's like a car now.”

And it’s a far cry from where the market is today. In the past decade, the median home price in Washington County jumped from $240,000 to $525,000.

Still, Merkley believes there is a path for potential buyers out there — if they can be flexible and patient.

“It's important to manage your expectations,” she said. “It is going to take time, and it is competitive.”

The market has cooled since its pandemic peak, she said, with homes typically taking twice as long to sell now as they did a few years ago. Still, high prices are keeping people — especially young adults — on the outside looking in. Nationwide, the average age of a first-time homebuyer hit an all-time high in 2025. It’s now 40 years old.

Her top advice is to talk with a real estate agent and mortgage lender to evaluate your financial situation and make a plan for reaching your goals. Don’t forget to factor in homeowners’ association fees and maintenance expenses when you’re estimating monthly costs. Then, save up by cutting any expenses you can.

“Look at the non-essentials,” Merkley said. “Are there luxuries that you have that you're paying for monthly, that you could do away with for a period of time that would get you closer?”

There’s also down payment assistance available from the state, the federal government and the Washington County Board of Realtors. Another option could be mutual self-help programs that allow people to put in sweat equity as they help build their own homes.

Personal budgeting is an important piece of the puzzle, said Switchpoint’s Hollowell. Her group offers free financial education classes to the people it works with. But in a market like Washington County, that can only get someone so far.

“We talk about budgeting, budgeting, budgeting,” Hollowell said. “But if you make $972 on Social Security and you're 88, how do you budget better?”

Hollowell’s team has seen a particular rise in older Utahns seeking services — people on fixed incomes who may have lived in the same apartment for 20 years and suddenly face eviction when rent jumps.

Even those who already own a home aren’t immune from these pressures, she said, because rising property values can increase taxes enough to strain someone’s budget.

To make housing realistically available to more Utahns, Hollowell said it’ll take big systemic solutions. That includes cities getting on board with higher-density housing. Or even considering non-market housing. That’s an idea cities like Vancouver and Vienna have tried to develop subsidized homes for moderate-income residents with prices that are set, rather than ones that rise with the market.

It’ll also take a change in mindset on the part of developers, she said — to be open to projects that help sustain the community, even if it means lower profit margins.

“Something's going to have to change, or else the system will break,” Hollowell said.

In the meantime, Stucki and plenty of other folks in southwest Utah are doing what they can to hang on.

Her rent was around $950 per month when she first moved in. It has since risen to $969, inching closer to her max. After experiencing homelessness a couple of years ago, she doesn't want to lose the stability this apartment has given her and her 16-year-old daughter.

“I’m nervous,” Stucki said, “just because I am a one-person income, and I do have my daughter here a majority of the time.”

She recently asked for — and got — a raise to make sure her budget pencils out going into the new year, now that Switchpoint’s rent support has ended. She’s not sure what she’d do if rent goes up again.

Despite how stressful the process of finding and keeping an apartment has felt at times, she wouldn’t trade it.

“Honestly, it was one of the best experiences I've had in my entire life, because I did it on my own,” Stucki said. “And then I can also show my daughter, ‘Hey, you can be a single mom — I don't want you to be a single mom — but you could be a single mom, and you can do it on your own.’ It's just hard work and dedication. Just not giving up.”

And she said nothing feels better than coming home.