The Salt Lake City School District is revisiting its cell phone policy for students. It's one of many districts across the nation trying to figure out how to handle the ever-present devices.

After surveying parents, students and teachers on the district’s current cell phone policy, the school board discussed it on April 16. Board member Bryan Jensen, who said he’s heard from a lot of his constituents about this topic, asked the board to take it up.

Earlier this year, Utah Gov. Spencer Cox asked schools “to remove cell phones during class time.” Cox highlighted Delta High School, which requires students to check their phones at the classroom door, and another junior high in the Granite School District that bans phones entirely.

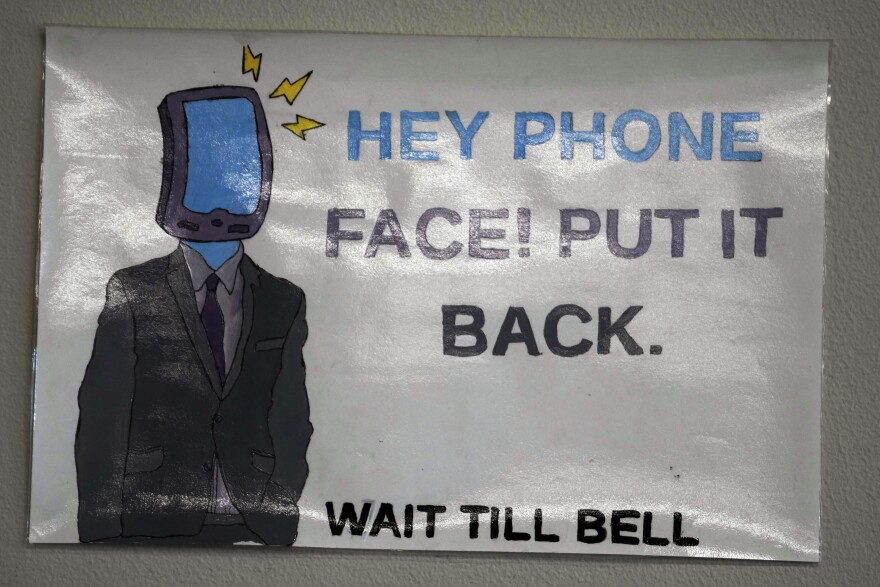

Salt Lake City School District’s current policy is not as strict. Students can bring their phones on campus, but each school within the district sets its own rules for how it can be used. The district’s policy does say cell phones are supposed to be off and put away during class unless a teacher says otherwise.

The district had thousands of responses to its survey, but it didn’t give board members a clear answer of what to do.

Not surprisingly, many of the students who responded were against a phone ban. That idea was more popular with parents, but there were concerns about being able to get in contact with their kids, such as in an emergency, for example.

“I think the most difficult piece of the survey was the disparate voices of parents because I think in order for this policy to be successful, we have to be in collaboration with parents, and parents have different needs,” said Superintendent Elizabeth Grant during the board meeting. “We’re in a tough position. It feels to me at this moment there isn’t a perfect answer.”

Some of the parents and teachers surveyed said they wanted the policy to be enforced more consistently. Some teachers also wanted clearer guidelines

The research on this issue also doesn’t provide a simple solution.

“The research, not surprisingly, is nuanced and mixed,” said BYU professor of human development Sarah Coyne.

Still, Coyne is grateful the governor is encouraging schools to have the conversation.

“I think that schools should be really thoughtful about their policies around cell phone use.”

Coyne said there’s some research to suggest getting cell phones out of schools would decrease distractions for students, which could improve test scores. It could also decrease cyberbullying, “which is a huge and very destructive problem during adolescence in particular.” Additionally, Coyne said, one study found students had higher anxiety on “mobile-free days.”

She added kids have gotten used to being able to contact their parents and “ a lot of students would struggle not being able to have that.” As the parent of a couple of kids with significant physical and mental health needs, she said her kids regularly check in with her. When there was a school shooting threat in her community last year, she was grateful to be able to communicate with her daughter.

In the Salt Lake City schools survey, 56.6% of high school parents said they communicate with their children one to three times a day during school.

Coyne said some students use their phones for connection, which they might turn to during the school day if they’re feeling marginalized or bullied.

During the meeting, board president Nate Salazar brought up the free SafeUT smartphone app, which students who are in a crisis can use to connect with a trained counselor or confidentially submit tips, like if they hear about a school shooting threat. Salazar said he could think of several instances where he believed the app “saved lives.”

Coyne said some educators also use phones for educational purposes.

That was pointed out during the meeting because 68% of high school teachers who responded said they allow students to use their phones in class for instructional reasons at least once a day. The majority of elementary and middle school teachers who responded said they never allow their students to use their phones.

While students are given laptops, board member Ashley Anderson said there are some high school classrooms where they can’t connect to WiFi so they use their phone data. If the district wants to change student behavior and limit how often they use phones during class, she said they need to provide different tools and better access.

If students are using their phones during class for schoolwork, which 22% of surveyed high schoolers said they were doing, Anderson said “that’s the category that we’re responsible for.”

High school student board member Jaziayah Evans said in her experience, students are more attached to their phones after the pandemic. Evans said she’s allowed to use her phone in all of her classes, which wasn’t the case before.

“I don’t have an answer or even close to a solution because there’s so many different factors.”

Her peers seem more socially reserved now, she said, so she sees a lot more people in the halls on their phones. She sees it as a safety blanket to avoid talking to others. And then there are the practical ways students use their phones, like saving passwords because it's easier to do that on a smartphone than a laptop.

Without a clear answer, the board decided to move the issue to its policy subcommittee to work through and look at how other districts across the country are handling this. They’ll bring the issue back to the full board after that.

Granite School District is also working through its phone policy. The school board discussed it in March and will bring it back up during its April 23 study session meeting.

Since the research is so nuanced, Coyne is not a fan of banning phones entirely. Since kids now use phones for so many different things, she thinks that the “ship has sailed.”

While Utah state lawmakers have talked before about whether to ban cell phones in classrooms, Coyne said she thinks the more important, but more difficult, question to be asking is “how can we help our youth thrive with this technology that is here, that is not going anywhere, and that can be used in some really powerful ways?”

Coyne thinks schools need to find a middle-ground approach. Such as Delta High School’s approach where students put their phones in a cubby or check them in once they enter a classroom.

“So it’s still in the room so you can use it if you need it, but you’re not just sitting there on TikTok the entire lesson,” Coyne said.