Salt Lake City made national news when Mayor Erin Mendenhall proposed that the city officially adopt the LGBTQ+ pride, trans and Juneteenth flags. It was a response to a new state law that defines which flags can fly on public buildings. Boise, Idaho, made the same move, but Salt Lake had a twist.

The city added sego lilies.

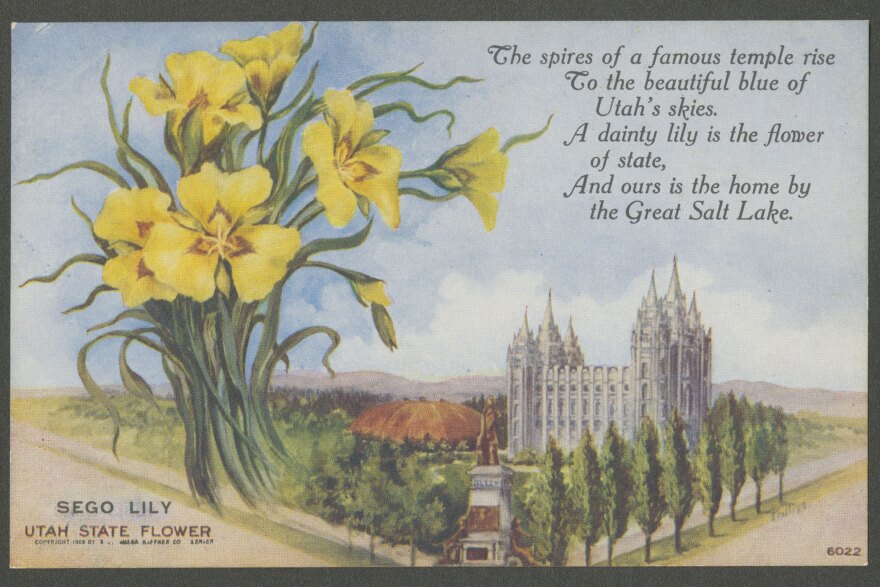

This is not the first time the humble sego lily has played a role in local and national politics. In fact, it has been a crucial part of people’s lives along the Wasatch Front for hundreds of years.

“We live in a core region of the sego lily range,” explained Mitchell James Power, the curator of botany at the Natural History Museum of Utah. “In any direction from Salt Lake, you will be in sego lily habitat.”

Power opened a door in a long row of metal cabinets in a sterile, climate-controlled collections room at the museum. Inside are around 100 sego lilies, dating back to 1888.

The 19th century was a challenging time for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1848, a year after the early pioneers arrived in the valley, a cricket infestation decimated fields of grain and vegetables. The Native Americans who lived there told the newcomers about which plants could be eaten.

Sego lilies grow in harsh, dry conditions — think sagebrush, bunch grass and patchy soil. And for native peoples, they were an important food source, providing a mildly sweet, nutty flavor. The word itself is believed to derive from the Shoshone for edible bulb. But at only about the size of a golf ball, it was a lot of work.

“When they are present in abundance, they can provide fairly substantial calories for people,” Power said. “You would probably need to collect, you know, several dozen of these to make a meal for an individual.”

The flower’s delicate bloom — commonly found with three white petals and purple and yellow core — took on a sacred meaning for Latter-day Saints, said historian Rebekah Clark.

“Brigham Young actually declared the Sego Lily as a heaven-sent source of food.”

Clark is the historical director for Better Days 2020, a group focused on Utah women’s history. And it was the women’s movement of the 19th century that secured the sego lily’s place as the state flower.

Those early pioneers had been driven west by political and religious persecution. And things hadn’t improved by the 1880s. National women’s groups had targeted what they called the “twin relics of barbarism” — slavery and polygamy. With the Civil War behind them, plural marriage was the focus of their fight for social purity.

The movement, Clark said, was a threat to the existence of the early church. But women in the Utah territory also secured the right to vote in 1870, which gave them an entrance into the national suffrage movement, and the National Council of Women, founded in 1888.

“It became a platform for women in Utah, Latter-day Saint women particularly, to be able to build commonality and build bridges and refute a lot of the national perceptions of Utah women,” Clark said.

It wasn’t just their reputation at stake. Utah was also seeking statehood for the seventh time, and women played an important part in proving the population’s “Americanness.”

One chance at that came at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. The national movement organized a coinciding convention called the World's Congress of Representative Women. The week included talks by Utah women to the assembly and a display of the state’s industry and refinement at the Utah Building.

As a symbol of unity, the national group envisioned a national garland of flowers. Each state would contribute a representative bloom to highlight their uniqueness, but also their strength as a collective.

The sego lily won the vote of Utah women, hands down.

“The bulbs really comes to symbolize this larger sense of tenacity and sacrifice and resilience, self-sufficiency that becomes this hallmark of the pioneer spirit,” Clark said.

The sego lily featured prominently in the Utah Building, embroidered in silks and lauded in poetry. And when Utah finally became a state in 1896, the flower was included in the state seal. Fifteen years later, it was enshrined as the state flower. It’s telling that the bill was just 16 words long.

But more than a century later, the sego lily had fallen out of fashion.

As Salt Lake City was looking for a flag design in 2020, the beehive tied to the state’s “Industry” motto was getting all the love. City leaders thought that, as the capital, it felt right to use a state symbol, but maybe not something quite so prominent. Today’s flag has a horizontal field of blue and one of white. Against the blue background, you’ll find the sego lily.

People have gotten behind the flag, said Lindsey Nikola, a Salt Lake City native and deputy chief of staff for the Salt Lake City Mayor’s Office. She also led the flag redesign effort. When she sees the lily on shirts and hats, it brings her as much joy as seeing them in the wild. She’s such an aficionado, she’s even gotten a sego lily tattoo and said others in city government have too.

“Recently, one thing that's really struck me is this symbolism of hardiness, of existing in very harsh conditions and continuing to be itself,” Nikola said.

“And I think that as a city and maybe even as a nation, a lot of people find themselves in a position where they feel similarly. They feel like they are going through things that they have never before gone through as people.”

Salt Lake City flies a historic state flag on Pioneer Day, and by recent tradition, they fly the Juneteenth flag, the LGBTQ+ pride flag and the transgender flag during times of commemoration and celebration. This clashed with the Legislature’s new law that limited the flags displayed at public buildings to a particular list — including the U.S. and state flag, and “a flag that represents a city, municipality, county, or political subdivision of the state.”

So Mayor Erin Mendenhall added the sego lily to each and made them official city banners. The city council unanimously agreed.

There has been criticism from conservatives. Speaker of the Utah House Mike Schultz called it political theater and a “clear waste of time and taxpayer resources.” And AFA Action, a Mississippi-based group focused on “biblical family values,” said the move “celebrates immoral and deviant behavior.”

But in her city council presentation, Mendenhall said, “In a time when so much uncertainty, so much fear threatens to divide us, our city symbols must leave no doubt that we are a united city and a united people.”

Meanwhile, the sego lily prepares to bloom. Power, the botanist, said the lilies spend most of their life underground. Their pulse begins in mid to late May and lasts only until early June.

“When that garden is flowering, you now have an experience with the lilies,” Power said.

“When I see them, I feel like that experience has been given to me at a very short period in time, and that it was my good fortune to get to see them in that window.”

Thanks to 12-year-old Blakely VanAusdal for her reading in the audio version of this story.