“What a waste of time.”

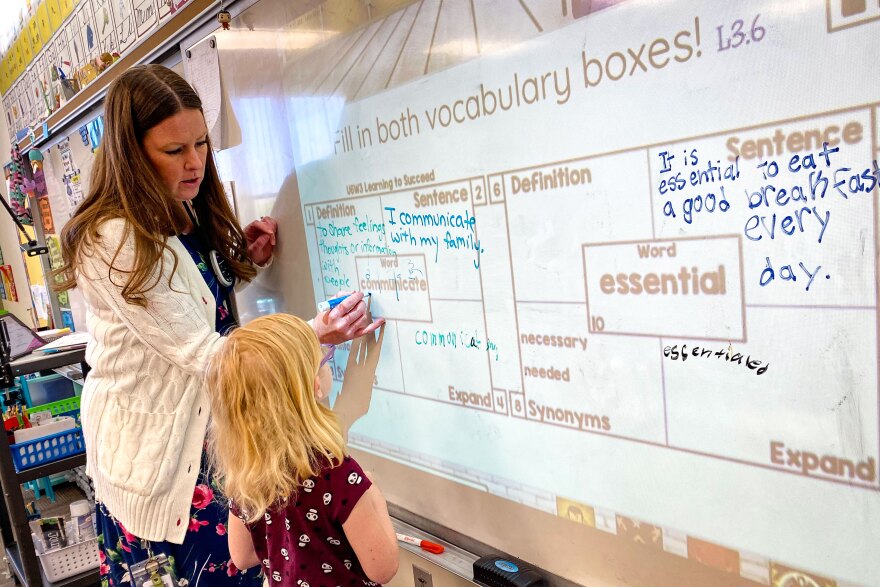

That was the thought third grade teacher Cassie White had when she first learned she’d be forced to start a new training program.

It was around January 2021, the second pandemic school year. Most kids in her district, Duchesne County, and her school, Centennial Elementary in Roosevelt, were back in class. Many were struggling, thanks in large part to COVID disruptions that impacted students across the state.

“This is where I feel like education [has] good intentions and poor execution,” she said. “They want to say, ‘Oh, we care about your wellness and your mental health. But we're going to load this on top of you.’ So clearly, they don't care.”

She had no choice. The training, the district said, would help White get her students back on track. At the time, about 25% of them were not reading at grade level. Somehow this year, the numbers are even worse. Close to 60% of her 23 students started the year behind.

The program was called LETRS, or Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling. It’s a series of books, online videos and tests on the fundamentals of reading instruction.

As White dove in, hoping initially to get it done as quickly as possible, she started to see how useful some of the lessons were. There were things she could start using in the classroom right away.

LETRS taught her that beginning readers need to understand how to break words down. It’s not simply deconstructing the syllables in a word and understanding which combinations of letters make particular sounds, but connecting the sounds and words with how they look written down.

She was already doing some of that, but she said the program helped her eliminate exercises that aren’t helpful — like word searches — and ensure she’s using techniques that have been proven to help kids learn to read.

“It has just kind of laid it out, ‘Do this, not this,’” she said. “And so it's just made me tweak things to make it so I feel like I'm doing research-based stuff instead of just fun, waste-of-time stuff.”

Recognizing the problem

Like many teachers across the country, White was not explicitly taught what researchers have known for decades is the science behind learning to read. That’s partly because it was perceived as tedious and some feared it would make kids dislike reading.

But over the years, more people started to pay attention to the research. Then came COVID-19, which created a sense of urgency to address widespread learning disruptions with a massive influx of federal funding to make it happen.

Sara Wiebke, a literacy coordinator with the Utah State Board of Education, said schools and teachers have been asking for help to teach reading since 2018. A survey of close to 4,000 teachers, along with hundreds of administrators, found that many did not feel confident teaching early literacy and they needed better, research-backed materials to use in the classroom.

“At that time we didn't have the funding to do anything about it,” Wiebke said. “And we admit that. But now [in 2021] we did. Let's try it. Let's see if it works. Some people might say the timing is horrible because everyone is so overwhelmed, and some people may say the timing is great because if you look at our data, it is not acceptable.”

So Utah became one of 18 states to revamp teacher preparation programs and retrain teachers on the science of reading. Using $12 million in federal COVID funding, the state launched an initial effort last year to train 8,000 teachers with LETRS, Cassie White included. Ninety districts and charter schools participated, Wiebke said.

This year, state lawmakers put up another $20 million to help finish the job. It’ll go toward more training, but also into hiring literacy coaches, convening a panel of experts to oversee the process and a requirement that districts use curriculum materials backed by the science of reading.

The goal is to get 70% of Utah third graders reading at grade level by 2027. Right now, just over half are.

The model is similar to one Mississippi launched in 2013, which is credited as at least part of the reason its fourth-grade reading scores jumped from 39th to 2nd in the nation by 2019. The state also, however, held struggling students back until they reached proficiency, which may also have been a significant factor in the increase.

Still, Wiebke said arming teachers with the knowledge around the science of reading is an important step toward improving outcomes. And at least anecdotally, she said it’s already leading to student growth.

High Hopes

Local experts also have high hopes for the undertaking. Kathleen Brown, who’s directed the University of Utah Reading Clinic since its inception in 1999, said she’s heartened to see that all of the key players needed for success are involved, from state lawmakers to higher education institutions, as well as a significant amount of funding.

While states have poured money into reading instruction over the decades, through efforts like No Child Left Behind, Brown said they haven't been game changers. She attributes that mostly to a lack of follow up. It’s one thing to give teachers books or lectures on a new skill. But it’s hard to make it stick without giving them the chance to observe others and get regular, ongoing feedback themselves.

“Think about the medical model,” she said. “Nobody says, ‘Here's a diagram of brain surgery. And now, good luck with that.’ It's all about approximating quality. That's what we really need in the field across the country and, of course, here in Utah.”

Brown said getting that component right is critical to making the project work.

While Cassie White’s school has a part-time reading coach, she has yet to receive any feedback. That may change next year when the coach becomes full-time.

In the meantime though, she said her students are making progress. Three-quarters of her class made above or well above growth on end-of-year tests.

It’s hard to know how much of that is due to the training she received. But at least now she knows the methods she uses work.

“I feel more confident,” she said. “Because it's not me just thinking I know. Research is backing up what I'm doing.”